Il testo originale è quello dell'edizione a cura di R. W. Chapman, pubblicata nel 1952 dalla Jane Austen Society.

|

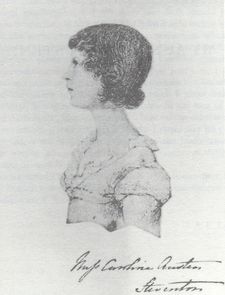

Jane Austen Caroline Austen |

|

Caroline Austen (1805-1880) era figlia di James, il fratello maggiore di JA, e di Mary Lloyd, la sua seconda moglie. Questi "ricordi", scritti nel 1867 e basati anche sul diario della madre, morta nel 1843, furono poi parzialmente citati nella biografia di JA scritta nel 1870 dal fratello, James-Edward Austen-Leigh. Il testo originale è quello dell'edizione a cura di R. W. Chapman, pubblicata nel 1952 dalla Jane Austen Society.

|

|

My Aunt Jane Austen. A Memoir

A memoir of Miss Jane Austen has often been asked for, and strangers have declared themselves willing and desirous to undertake the task of writing it - and have wondered that the family should have refused to supply the necessary materials. But tho' none of the nearest relatives desired that the details of a very private and rather uneventful life should be laid before the world yet I think they would not willingly have had her memory die - and it will die and be lost, if no effort is made to preserve it - The grass grave in the village churchyard sinks down in a few years to the common level, and its place is no more to be found and so, to keep the remembrance of the departed a little longer in the world which they have left, we lay a stone over their graves, and inscribe upon it their name and age, and perhaps some few words of their virtues and of our own sorrow - and tho' the stone moulders and tho' the letters fade away, yet do they outlast the interest of what they record - We remember our dead always - but when we shall have joined them their memory may be said to have perished out of the earth - for no distinct idea of them remains behind, and the next generation soon forget that they ever existed - For most of us therefore, the memorial on the perishing tombstone is enough - and more than enough - it will tell its tale longer than anyone will care to read it - But not so for all - Every country has had its great men, whose lives have been and are still read - with unceasing interest; and so, in some families there has been one distinguished by talent or goodness, and known far beyond the home circle, whose memory ought to be preserved through more than a single generation - Such a one was my Aunt - Jane Austen - Since her death, the public voice has placed her in the first rank of the Novellists of her day - given her, I may say, the first place amongst them - and it seems but right that some record should remain with us of her life and character; and that she herself should not be forgotten by her nearest descendants, whilst her writings still live, and are still spreading her fame wherever the English books are read. - Her last long surviving Brother has recently died at the age of 91 (1865) - The generation who knew her is passing away - but those who are succeeding us must feel an interest in the personal character of their Great Aunt, who has made the family name in some small degree, illustrious - For them therefore, and for my own gratification I will try to call back my recollections of what she was, and what manner of life she led - It is not much that I have to tell - for I mean to relate only what I saw and what I thought myself - I was just twelve years old when she died - therefore, I knew her only with a child's knowledge -

My first very distinct remembrance of her is in her own home at Chawton - The house belonged to her second brother, Mr. Knight (of Godmersham & Chawton) and was by him made a comfortable residence for his mother and sisters - The family party there were, my grandmother, Mrs. Austen - my two aunts, her daughters - and a third aunt of mine - Miss Lloyd, who had made her home with them before I can remember, and who remained their inmate as long as Mrs. Austen lived - The dwelling place of a favourite author always possesses a certain interest for those who love the books that issued from it - Tho' some of my aunt's novels were imagined and written in her very early days - some certainly at Steventon yet it was from Chawton that after being rearranged and prepared for publication they were sent out into the world - and it is with Chawton therefore, that her name as an author, must be identified - The house which she inhabited was in itself, not much more deserving of notice than Cowper's dwelling place at Olney - and yet more than 30 years after his death, that was pointed out to us, as a something that strangers passing through the little town, must wish to see - Now, as the remembrance of Chawton Cottage, for so in later years it came to be called, is still pleasant to me - I will assume that those who never knew it, may like to have laid before them, a description of their Aunt's home - the last that she dwelt in - where, in the maturity of her mind, she completed the works that have given her an English name - where after a few years, whilst still in the prime of life, she began to droop and wither away - the home from whence she removed only in the last stage of her illness, by the persuasion of her friends, hoping against hope - and to which her sister before long had to return alone - My Grand Father, Mr. Austen, held for many years, the adjoining livings of Deane and Steventon - but gave up his duties to his eldest son, and settled at Bath, a very few years before his own death - For a while, his widow and daughters remained at Bath - then they removed to Southampton - and finally settled in the village of Chawton - Mr. Knight had been able to offer his mother the choice of two houses - one in Kent near to Godmersham - and the other at Chawton - and she and her daughters eventually decided on the Hampshire residence. I have been told I know not how truthfully, that it had been originally a roadside Inn - and it was well placed for such a purpose - just where the road from Winchester comes into the London and Gosport line - The fork between the two being partly occupied by a large shallow pond - which pond I beleive has long since become dry ground - The front door opened on the road, a very narrow enclosure of each side protected the house from the possible shock of any runaway vehicle - A good sized entrance, and two parlours called dining and drawing room, made the length of the house; all intended originally to look on the road - but the large drawing room window was blocked-up and turned into a bookcase when Mrs. Austen took possession and another was opened at the side, which gave to view only turf and trees - a high wooden fence shut out the road (the Winchester road it was) all the length of the little domain, and trees were planted inside to form a shrubbery walk - which carried round the enclosure, gave a very sufficient space for exercise - you did not feel cramped for room; and there was a pleasant irregular mixture of hedgerow, and grass, and gravel walk and long grass for mowing, and orchard - which I imagine arose from two or three little enclosures having been thrown together, and arranged as best might be, for ladies' occupation - There was besides a good kitchen garden, large court and many out-buildings, not much occupied - and all this affluence of space was very delightful to children, and I have no doubt added considerably to the pleasure of a visit - Everything indoors and out was well kept - the house was well furnished, and it was altogether a comfortable and ladylike establishment, tho' I beleive the means which supported it, were but small - The house was quite as good as the generality of Parsonage houses then - and much in the same old style - the ceilings low and roughly finished - some bedrooms very small - none very large but in number sufficient to accomodate the inmates, and several guests - The dining room could not be made to look anywhere but on the road - and there my grandmother often sat for an hour or two in the morning, with her work or her writing - cheered by its sunny aspect and by the stirring scene it afforded her. I beleive the close vicinity of the road was really no more an evil to her than it was to her grandchildren. Collyer's daily coach with six horses was a sight to see! and most delightful was it to a child to have the awful stillness of night so frequently broken by the noise of passing carriages, which seemed sometimes, even to shake the bed - The village of Chawton has, of course, long since been tranquilised - it is no more a great thoroughfare, and other and many changes have past over it - and if any of its visitants should fail to recognise from my description, the house by the pond - I must beg them not hastily to accuse me of having exaggerated its former pleasantness. Twenty years ago, on being then left vacant by Aunt Cassandra's death, it was divided into habitations for the poor, and made to accomodate several families - so I was told - for I have never seen it since and I beleive trees have been cut down, and all that could be termed pleasure ground has reverted again to more ordinary purposes - My visits to Chawton were frequent - I cannot tell when they began - they were very pleasant to me - and Aunt Jane was the great charm - As a very little girl, I was always creeping up to her, and following her whenever I could, in the house and out of it - I might not have remembered this, but for the recollection of my mother's telling me privately, I must not be troublesome to my aunt - Her charm to children was great sweetness of manner - she seemed to love you, and you loved her naturally in return - This as well as I can now recollect and analyse, was what I felt in my earliest days, before I was old enough to be amused by her cleverness - But soon came the delight of her playful talk - Everything she could make amusing to a child - Then, as I got older, and when cousins came to share the entertainment, she would tell us the most delightful stories chiefly of Fairyland, and her Fairies had all characters of their own - The tale was invented, I am sure, at the moment, and was sometimes continued for 2 or 3 days, if occasion served - As to my Aunt's personal appearance, her's was the first face that I can remember thinking pretty, not that I used that word to myself, but I know I looked at her with admiration - Her face was rather round than long - she had a bright, but not a pink colour - a clear brown complexion and very good hazle eyes -She was not, I beleive, an absolute beauty, but before she left Steventon she was established as a very pretty girl, in the opinion of most of her neighbours - as I learned afterwards from some of those who still remained - Her hair, a darkish brown, curled naturally - it was in short curls round her face (for then ringlets were not.) She always wore a cap - Such was the custom with ladies who were not quite young - at least of a morning but I never saw her without one, to the best of my remembrance, either morning or evening. I beleive my two Aunts were not accounted very good dressers, and were thought to have taken to the garb of middle age unnecessarily soon - but they were particularly neat, and they held all untidy ways in great disesteem. Of the two, Aunt Jane was by far my favourite - I did not dislike Aunt Cassandra - but if my visit had at any time chanced to fall out during her absence, I don t think I should have missed her - whereas, not to have found Aunt Jane at Chawton, would have been a blank indeed. As I grew older, I met with young companions at my Grandmother's - Of Capt. Charles Austen's motherless girls, one the eldest, Cassy - lived there chiefly, for a time - under the especial tutorage of Aunt Cassandra; and then Chawton House was for a while inhabited by Capt. Frank Austen; and he had many children - I beleive we were all of us, according to our different ages and natures, very fond of our Aunt Jane - and that we ever retained a strong impression of the pleasantness of Chawton life - One of my cousins, now long since dead, after he was grown up, used occasionally to go and see Aunt Cass. - then left sole inmate of the old house - and he told me once, that his visits were always a disappointment to him - for that he could not help expecting to feel particularly happy at Chawton and never till he got there, could he fully realise to himself how all its peculiar pleasures were gone - In the time of my childhood, it was a cheerful house - my Uncles, one or another, frequently coming for a few days; and they were all pleasant in their own family - I have thought since, after having seen more of other households, wonderfully, as the family talk had much of spirit and vivacity, and it was never troubled by disagreements as it was not their habit to argue with each other - There always was perfect harmony amongst the brothers and sisters, and over my Grandmother's door might have been inscribed the text, "Behold how good - and joyful a thing it is, brethren, to dwell together in unity." There was firm family union, never broken but by death - tho' the time came when that union could not have been preserved if natural affection had not been by a spirit of forbearance and generosity - Aunt Jane began her day with music - for which I conclude she had a natural taste; as she thus kept it up - tho' she had no one to teach; was never induced (as I have heard) to play in company; and none of her family cared much for it. I suppose, that she might not trouble them, she chose her practising time before breakfast - when she could have the room to herself - She practised regularly every morning - She played very pretty tunes, I thought - and I liked to stand by her and listen to them; but the music, (for I knew the books well in after years) would now be thought disgracefully easy - Much that she played from was manuscript, copied out by herself - and so neatly and correctly, that it was as easy to read as print - At 9 o'clock she made breakfast - that was her part of the household work - The tea and sugar stores were under her charge - and the wine - Aunt Cassandra did all the rest - for my Grandmother had suffered herself to be superseded by her daughters before I can remember; and soon after, she ceased even to sit at the head of the table - I don't beleive Aunt Jane observed any particular method in parcelling out her day but I think she generally sat in the drawing room till luncheon: when visitors were there, chiefly at work - She was fond of work - and she was a great adept at overcast and satin stitch - the peculiar delight of that day - General handiness and neatness were amongst her characteristics - She could throw the spilikens for us, better than anyone else, and she was wonderfully successful at cup and ball - She found a resource sometimes in that simple game, when she suffered from weak eyes and could not work or read for long together - Her handwriting remains to bear testimony to its own excellence; and every note and letter of hers, was finished off handsomely - There was an art then in folding and sealing - no adhesive envelopes made all easy - some people's letters looked always loose and untidy - but her paper was sure to take the right folds, and her sealing wax to drop in the proper place - After luncheon, my Aunts generally walked out - sometimes they went to Alton for shopping - Often, one or the other of them, to the Great House - as it was then called - when a brother was inhabiting it, to make a visit - or if the house were standing empty they liked to stroll about the grounds - sometimes to Chawton Park - a noble beech wood, just within a walk - but sometimes, but that was rarely, to call on a neighbour - They had no carriage, and their visitings did not extend far - there were a few familities living in the village - but no great intimacy was kept up with any of them - they were upon friendly but rather distant terms, with all - Yet I am sure my Aunt Jane had a regard for her neighbours and felt a kindly interest in their proceedings. She liked immensely to hear all about them. They sometimes served for her amusement, but it was her own nonsense that gave zest to the gossip - She never turned them into ridicule - She was as far as possible from being either censorious or satirical - she never abused them or quizzed them - That was the word of the day - an ugly word, now obsolete - and the ugly practise which it bespoke, is far less prevalent now, under any name, than it was then. The laugh she occasionally raised was by imagining for her neighbours impossible contingencies - by relating in prose or verse some trifling incident coloured to her own fancy, or in writing a history of what they had said or done, that could deceive nobody - As an instance I would give her description of the pursuits of Miss Mills and Miss Yates - two young ladies of whom she knew next to nothing - they were only on a visit to a near neighbour but their names tempted her into rhyme - and so on she went - This was before my time. Mrs. Lefroy knows the lines better than I do - I beleive she has a copy and I shall not attempt to quote them imperfectly here. To about the same date perhaps may be referred (at least it was equally before my time) a few chapters which I overheard - of a mock heroic story, written between herself and one of her nieces, and I doubt not, at her instigation - If I remember rightly, it had no other foundation than their having seen a neighbour passing on the coach, without having previously known that he was going to leave home - (This I have since been told was written entirely by the niece only under her encouragement). I did not often see my Aunt with a book in her hand, but I beleive she was fond of reading and that she had read and did read a good deal. I doubt whether she cared very much for poetry in general; but she was a great admirer of Crabbe, and consequently she took a keen interest in finding out who he was - Other contemporary writers were well-known, but his origen having been obscure, his name did not announce itself - however by diligent enquiry she was ere long able to inform the rest of the family that he held the Living of Trowbridge, and had recently married a second time - A very warm admirer of my Aunt's writing but a stranger in England, lately made the observation that it would be most interesting to know what had been Miss Austen's opinion on the great public events of her time - a period as she rightly observed, of the greatest interest - for my Aunt must have been a young woman, able to think, at the time of the French Revolution. The long disastrous chapter then begun, was closed by the battle of Waterloo, two years before her death - anyone might naturally desire to know what part such a mind as her's had taken in the great strifes of war and policy which so disquieted Europe for more than 20 years - and yet, it was a question that had never before presented itself to me - and tho' I have now retraced my steps on this track, I have found absolutely nothing! The general politics of the family were Tory - rather taken for granted I suppose, than discussed, as even my Uncles seldom talked about it - and in vain do I try to recall any word or expression of Aunt Jane's that had reference to public events - Some bias of course she must have had - but I can only guess to which quarter it inclined - Of her historical opinions I am able to record thus much - that she was a most loyal adherent of Charles the 1st, and that she always encouraged my youthful beleif in Mary Stuart's perfect innocence of all the crimes with which History has charged her memory - My Aunt must have spent much time in writing - her desk lived in the drawing room. I often saw her writing letters on it, and I beleive she wrote much of her Novels in the same way - sitting with her family, when they were quite alone; but I never saw any manuscript of that sort, in progress - She wrote very fully to her Brothers when they were at sea, and she corresponded with many others of her family - There is nothing in those letters which I have seen that would be acceptable to the public - They were very well expressed, and they must have been very interesting to those who received them - but they detailed chiefly home and family events: and she seldom committed herself even to an opinion - so that to strangers they could be no transcript of her mind - they would not feel that they knew her any the better for having read them - They were rather over-cautious, for excellence - Her letters to Aunt Cassandra (for they were sometimes separated) were, I dare say, open and confidential - My Aunt looked them over and burnt the greater part, (as she told me), 2 or 3 years before her own death - She left, or gave some as legacies to the Nieces - but of those that I have seen, several had portions cut out - Aunt Jane was so good as frequently to write to me; and in addressing a child, she was perfect - When staying at Chawton, if my two cousins, Mary Jane and Cassy were there, we often had amusements in which my Aunt was very helpful - She was the one to whom we always looked for help - She would furnish us with what we wanted from her wardrobe, and she would often be the entertaining visitor in our make beleive house - She amused us in various ways - once I remember in giving a conversation as between myself and my two cousins, supposed to be grown up, the day after a Ball. As I grew older, she would talk to me more seriously of my reading, and of my amusements - I had taken early to writing verses and stories, and I am sorry to think how I troubled her with reading them. She was very kind about it, and always had some praise to bestow but at last she warned me against spending too much time upon them - She said - how well I recollect it! that she knew writing stories was a great amusement, and she thought a harmless one - tho' many people, she was aware, thought otherwise - but that at my age it would be bad for me to be much taken up with my own compositions - Later still - it was after she got to Winchester, she sent me a message to this effect - That if would take her advice, I should cease writing till I was 16, and that she had herself often wished she had read more, and written less, in the corresponding years of her own life. She was considered to read aloud remarkably well. I did not often hear her but once I knew her take up a volume of Evelina and read a few pages of Mr. Smith and the Brangtons and I thought it was like a play. She had a very good speaking voice - This was the opinion of her contemporaries - and though I did not then think of it as a perfection, or ever hear it observed upon, yet its tones have never been forgotten - I can recall them even now - and I know they were very pleasant. I have spoken of the family union that prevailed amongst my Grandmother's children - Aunt Jane was a very affectionate sister to all her brothers - One of them in particular was her especial pride and delight: but of all her family, the nearest and dearest throughout her whole life was, undoubtedly her sister - her only sister. Aunt Cassandra was the older by 3 or 4 years, and the habit of looking up to her begun in childhood, seemed always to continue - When I was a little girl, she would frequently say to me, if opportunity offered, that Aunt Cassandra could teach everything much better than she could - Aunt Cass. knew more - Aunt Cass. could tell me better whatever I wanted to know - all which, I ever received in respectful silence - Perhaps she thought my mind wanted a turn in that direction, but I truly beleive she did always really think of her sister, as the superior to herself. The most perfect affection and confidence ever subsisted between them - and great and lasting was the sorrow of the survivor when the final separation was made - My Aunt's life at Chawton, as far as I ever knew, was an easy and pleasant one - it had little variety in it, and I am not aware of any particular trials, till her own health began to fail - She stayed from home occasionally - almost entirely with the families of her different brothers - In the Autumn of 1815 she was in London, with my Uncle, Mr. Henry Austen, then living in Hans Place - and a widower - During her visit, he was seized with low fever and became so ill that his life was despaired of, and Aunt Cassandra and my Father were summoned to the house - there, for a day or two, they hourly expected his death - but a favourable turn came, and he began to recover - My Father then went home. Aunt Cass. stayed on nearly a month, and Aunt Jane remained some weeks longer, to nurse the convalescent - It was during this stay in London, that a little gleam of Court favor shone upon her. She had at first published her novels with a great desire of remaining herself unknown - but it was found impossible to preserve a secret that so many of the family knew and by this time, she had given up the attempt - and her name had been made public enough - tho' it was never inserted in the title page - Two of the great Physicians of the day had attended my Uncle during his illness - I am not, at this distance of time, sufficiently sure which they were, as to give their names, but one of them had very intimate access to the Prince Regent, and continuing his visits during my Uncle's recovery, he told my Aunt one day, that the Prince was a great admirer of her novels: that he often read them, and had a set in each of his residences - That he, the physician had told his Royal Highness that Miss Austen was now in London, and that by the Prince's desire, Mr. Clarke, the Librarian of Carlton House, would speedily wait upon her - Mr. Clarke came, and endorsed all previous compliments, and invited my Aunt to see Carlton House, saying the Prince had charged him to show her the Library there, adding many civilities as to the pleasure his R.H. had received from her novels - Three had then been published - The invitation could not be declined - and my Aunt went, at an appointed time, to Carlton House - She saw the Library, and I beleive, some other apartments, but the particulars of her visit, if I ever heard them, I have now forgotten - only this, I do well recollect - that in the course of it, Mr. Clarke, speaking again of the Regent's admiration of her writing, declared himself charged to say, that if Miss Austen had any other novel forthcoming, she was quite at liberty to dedicate it to the Prince. My Aunt made all proper acknowledgments at the moment, but had no intention of accepting the honor offered - until she was advised by some of her friends that she must consider the permission as a command - Emma was then in the Publisher's hands - so a few lines of dedication were affixed to the 1st volume, and following still the instructions of the well informed, she sent a copy, handsomely bound, to Carlton House - and I suppose it was duly acknowledged by Mr. Clarke - My Aunt, soon after her visit to him, returned home, where the little adventure was talked of for a while with some interest, and afforded some amusement - In the following Spring, Mr. Henry Austen ceased to reside in London, and my Aunt was never brought so near the precints of the Court again - nor did she ever try to recall herself to the recollection of Physician, Librarian or Prince, and so ended this little burst of Royal Patronage. I beleive Aunt Jane's health began to fail some time before we knew she was really ill - but she became avowedly less equal to exercise. In a letter to me she says: "I have taken one ride on the donkey and I like it very much, and you must try to get me quiet mild days that I may be able to go out pretty constantly - a great deal of wind does not suit me, as I have still a tendency to rheumatism. In short, I am but a poor Honey at present - I will be better when you can come and see us." - A donkey carriage had been set up for my Grandmother's accomodation - but I think she seldom used it, and Aunt Jane found it a help to herself in getting to Alton - where, for a time, Capt. Austen had a house, after removing from his Brother's place at Chawton. - In my later visits to Chawton Cottage, I remember Aunt Jane used often to lie down after dinner - My Grandmother herself was frequently on the sofa - sometimes in the afternoon, sometimes in the evening, at no fixed period of the day, - She had not bad health for her age, and she worked often for hours in the garden, and naturally wanted rest afterwards - There was only one sofa in the room - and Aunt Jane laid upon 3 chairs which she arranged for herself - I think she had a pillow, but it never looked comfortable - She called it her sofa, and even when the other was unoccupied, she never took it - It seemed understood that she preferred the chairs - I wondered and wondered - for the real sofa was frequently vacant, and still she laid in this comfortless manner - I often asked her how she could like the chairs best - and I suppose I worried her into telling me the reason of her choice - which was, that if she ever used the sofa, Grandmama would be leaving it for her, and would not lie down, as she did now, whenever she felt inclined - In May, 1816 my two Aunts went for a few weeks to Cheltenham - I am able to ascertain the date of this, and some similar occurrences by a reference to old pocket books in my possession - It was a journey in those days, to go from Hampshire into Gloucestershire and their first stage was to Steventon - They stayed one whole day, and left my Cousin Cassy to remain with us during their absence - They made also a short stay at Mr. Fowle's at Kintbury I believe that was, as they returned - Mrs. Dexter, then Mary Jane Fowle, told me afterwards, that Aunt Jane went over the old places, and recalled old recollections associated with them, in a very particular manner - looked at them, my cousin thought, as if she never expected to see them again - The Kintbury family, during that visit, received an impression that her health was failing - altho' they did not know of any particular malady. The year 1817, the last of my Aunt's life, began it seems under good auspices. I copy from a letter of her's to myself dated Jany. 23rd - 1817 - the only letter I have which does bear the date of the year - "I feel myself getting stronger than I was - and can so perfectly well walk to Alton, or back again, without the slightest fatigue that I hope to be able to do both, when summer comes -" I do not know when the alarming symptoms of her malady came on - It was in the following March that I had the first idea of her being seriously ill - It had been settled that about the end of that month, or the beginning of April, I should spend a few days at Chawton, in the absence of my Father and Mother, who were just then engaged with Mrs. Leigh Perrot in arranging her late husband's affairs - it was shortly after Mr. Leigh Perrot's death - but Aunt Jane became too ill to have me in the house, and so I went instead to my sister, Mrs. Lefroy, at Wyards - The next day we walked over to Chawton to make enquiries after our Aunt - She was keeping her room but said she would see us, and we went up to her - She was in her dressing gown and was sitting quite like an invalide in an arm chair - but she got up, and kindly greeted us - and then pointing to seats which had been arranged for us by the fire, she said, "There's a chair for the married lady, and a little stool for you, Caroline." - It is strange, but those trifling words are the last of her's that I can remember - for I retain no recollection at all of what was said by any one in the conversation that of course ensued - I was struck by the alteration in herself - She was very pale - her voice was weak and low and there was about her, a general appearance of debility and suffering; but I have been told that she never had much actual pain - She was not equal to the exertion of talking to us, and our visit to the sick room was a very short one - Aunt Cassandra soon taking us away - I do not suppose we stayed a quarter of an hour; and I never saw Aunt Jane again - I think she must have been particularly ill that day, and that in some degree she afterwards rallied - I soon went home again - but I beleive Mrs. Lefroy saw her more than once afterwards before she went to Winchester - It was sometime in the following May, that she removed thither - Better medical advice was needed, then Alton could supply - Not I beleive with much hope that any skill could effect a cure but from the natural desire of her family to place her in the best hands - Mr. Lyford was thought to be very clever so much so, as to be generally summoned far beyond his own practise - to give his opinion in cases of serious illness - In the earlier stages of her malady, my Aunt had had the advice, in London, of one of the eminent physicians of the day - Aunt Cassandra, of course, accompanied her sister and they had lodgings in College Street - Their great friends Mrs. Heathcote and Miss Bigg, then living in The Close, had made all the arrangements for them, and did all they could to promote their comfort during that melancholy sojourn in Winchester. Mr. Lyford could give no hope of recovery - He told my Mother that the duration of the illness must be very uncertain - it might be lingering or it might, with equal probability come to a sudden close - and that he feared the last period, whenever it arrived, would be one of severe suffering - but this was mercifully ordered otherwise - My mother, after a little time, had joined her sisters-in-law - to make it more cheerful for them, and also to take a share in the necessary attendance - From her, therefore, I learned, that my Aunt's resignation and composure of spirit were such, as those who knew her well, would have hoped for and expected - She was a humble and beleiving Christian; her life had passed in the cheerful performance of all home duties, and with no aiming at applause, she had sought, as if by instinct to promote the happiness of all those who came within her influence - doubtless she had her reward, in the peace of mind which was granted to her in her last days - She was quite aware of her own danger - it was no delusive hope that kept up her spirits - and there was everything to attach her to life - Tho' she had passed by the hopes and enjoyments of youth, yet its sorrows also were left behind - and Autumn is sometimes so calm and fair that it consoles us for the departure of Spring and Summer - and thus it might have been with her - She was happy in her family and in her home, and no doubt the exercise of her great talent, was a happiness also in itself - and she was just learning to feel confidence in her own success - In no human mind was there less of vanity than in her's - yet she could not but be pleased and gratified as her works, by slow degrees made their way in the world, with constantly increasing favour - She had no cause to be weary of life, and there was much to make it very pleasant to her - We may be sure she would fain have lived on - yet she was enabled, without complaint, and without dismay, to prepare for death - She had for some time known that it might be approaching her; and now she saw it with certainty, to be very near at hand. The religious services most suitable to her state were ministered to her, during this, the last stage of her illness - sometimes by a Brother - Two of them were Clergymen and at Winchester she was within easy distance of both - Her sweetness of temper never failed her; she was considerate and grateful to those who attended on her, and at times, when feeling rather better, her playfulness of spirit prevailed, and she amused them even in their sadness - A Brother frequently went over for a few hours, or a day or two - Suddenly she became much worse - Mr. Lyford thought the end was near at hand, and she beleived herself to be dying - and under this conviction she said all that she wished to say to those around her - In taking then, as she thought, a last leave of my Mother, she thanked her for being there, and said, "You have always been a kind sister to me, Mary." - Contrary to any expectation, the immediate danger passed away; she became comfortable again, and seemed really better - My Mother then came home - but not for long, as she was shortly summoned back - This was from no increase of my Aunt's illness, but because the Nurse could not be trusted for her share of the night attendance, having been more than once found asleep - so to relieve her from that part of her charge, Aunt Cassandra and my Mother and my Aunt's maid took the nights between them. Aunt Jane continued very cheerfully and comfortable, and there began to be a hope of, at least, a respite from death - But soon, and suddenly, as it were, a great change came on - not apparently, attended with much suffering - she sank rapidly - Mr. Lyford - when he saw her, could give no further hope, and she must have felt her own state - for when he asked her if there was anything she wanted, she replied, "Nothing but death." Those were her last words - They watched by her through the night, and in quietness and peace she breathed her last on the morning of the 18th of July, 1817 - I need scarcely say she was dearly loved by her family - Her Brothers were very proud of her - Her literary fame, at the close of her life, was only just spreading - but they were proud of her talents, which they even then estimated highly - proud of her home virtues, of her cheerful spirit - of her pleasant looks - and each loved afterwards to fancy a resemblance in some daughter of his own, to the dear "Aunt Jane", whose perfect equal they yet never expected to see - March 1867 - Written out, |

Mia zia Jane Austen. Ricordi

Spesso si è sentito il bisogno di una biografia di Miss Jane Austen, e diversi estranei hanno espresso la disponibilità e il desiderio di assumersi il compito di scriverla, e si sono meravigliati che la famiglia si sia rifiutata di fornire il materiale necessario. Ma anche se nessuno dei parenti più stretti ha mai desiderato che i dettagli di una vita molto riservata e quasi priva di eventi fossero rivelati al mondo, credo che non avrebbero voluto vedere estinto il ricordo di lei; e si estinguerà, e andrà perso, se non si fa nessuno sforzo per preservarlo. La tomba in un villaggio di campagna sparisce in pochi anni, e diventa indistinguibile, così, per mantenere ancora per un po' il ricordo dei defunti nel mondo che hanno lasciato, mettiamo una lapide sulle loro tombe, ci scriviamo il nome e l'età, e forse qualche parola sulle loro virtù e sul nostro dolore, e anche se la lapide si sgretola e le lettere svaniscono, permettono comunque di prolungare la conoscenza di ciò che rammentano. Noi ricordiamo per sempre i nostri morti, ma quando li raggiungeremo si può dire che la loro memoria si estinguerà in questo mondo, poiché non rimarrà nessuna idea precisa di loro, e le successive generazioni dimenticheranno che siano mai esistiti. Per la maggior parte di noi, quindi, il monumento sulla tomba degli estinti è sufficiente, più che sufficiente, e preserverà il suo racconto più a lungo di quanto possa interessare a qualcuno leggerlo. Ma non per tutti è così. Ogni paese ha i suoi grandi uomini, le cui vite sono state e sono ancora lette, con incessante interesse; e allo stesso modo, in alcune famiglie c'è stato qualcuno che si è distinto per talenti o bontà, ed è conosciuto ben al di là della cerchia familiare, la cui memoria deve essere preservata attraverso più di una singola generazione. Tale è stata mia zia Jane Austen. Dalla sua morte, il pubblico l'ha inserita in prima fila tra i romanzieri del suo tempo, assegnandole, posso dirlo, il primo posto tra di loro; e non può che essere giusto che almeno qualche ricordo resti tra noi della sua vita e del suo carattere, e che lei stessa non sia dimenticata dai suoi discendenti più prossimi, mentre le sue opere ancora vivono, e ancora diffondono la sua fama ovunque siano letti libri inglesi. L'ultimo suo fratello sopravvissuto è morto recentemente all'età di 91 anni (1865). (1) La generazione che l'ha conosciuta è scomparsa, ma quelli che verranno dopo di noi devono provare interesse per la persona della loro prozia, che ha reso in qualche modo illustre il nome della famiglia. Per loro, quindi, e a mia stessa soddisfazione, cercherò di richiamare alla mente i miei ricordi di ciò che è stata, e di che tipo di vita ha condotto. Quello che ho da dire non è molto, poiché intendo riferire solo quello che ho visto e che ho pensato io stessa. Avevo appena dodici anni quando lei morì, e quindi la mia conoscenza di lei è stata quella di una bambina.

Il primo ricordo distinto che ho di lei è nella sua casa a Chawton. La casa apparteneva al suo secondo fratello, Mr. Knight (di Godmersham e Chawton) (2) ed era stata sistemata in modo da diventare una residenza confortevole per la madre e le sorelle. La famiglia era allora composta da mia nonna, Mrs. Austen, dalle mie due zie, sue figlie, e da una terza mia zia, Miss Lloyd, che era andata a vivere con loro prima di quanto io possa ricordare, e che rimase loro ospite fino a quando visse Mrs. Austen. (3) Il luogo in cui è vissuto un autore prediletto possiede sempre un certo interesse per quelli che amano i libri che ne sono scaturiti. Sebbene alcuni dei romanzi di mia zia furono ideati e scritti quando era molto giovane, alcuni certamente a Steventon, fu in effetti da Chawton che, dopo essere stati rivisti e preparati per la pubblicazione, furono rivelati al mondo, ed è quindi con Chawton che il suo nome come autrice dev'essere identificato. (4) La casa in cui visse era in sé non molto più degna di nota di quella di Cowper a Olney, (5) dove, dopo più di trent'anni dalla sua morte, ci venne indicata come qualcosa che chiunque passasse per la cittadina dovesse vedere. Dato che il ricordo del Chawton Cottage, così in anni recenti si è cominciato a chiamarlo, è ancora adesso così piacevole per me, presumo che a coloro che non l'hanno mai visto possa far piacere di avere una descrizione della casa della loro zia, l'ultima in cui visse; dove, nella piena maturità, completò le opere che le hanno conferito la fama di autrice inglese; dove dopo qualche anno, mentre era ancora nel fiore della vita, iniziò ad appassire e a spegnersi; la casa dalla quale si mosse solo nell'ultimo stadio della sua malattia, convinta dai suoi parenti, sperando al di là di ogni speranza, e alla quale la sorella dopo non molto dovette tornare da sola. Mio nonno, Mr. Austen, mantenne per molti anni i benefici ecclesiastici confinanti di Deane e Steventon, ma rinunciò ai suoi doveri in favore del figlio maggiore, e si sistemò a Bath, pochi anni prima della sua morte. Per qualche tempo, la vedova e le figlie rimasero a Bath, poi si trasferirono a Southampton, e infine si sistemarono a Chawton. Mr. Knight era stato in grado di offrire alla madre la scelta tra due case, una nel Kent vicino a Godmersham, e l'altra a Chawton, e lei e le figlie decisero per quella nell'Hampshire. Mi è stato detto, ma non so se corrisponde al vero, che era stata all'origine una locanda di passaggio, ed era in una buona posizione per esserlo, proprio dove la strada da Winchester incrociava quella per Londra e Gosport. L'incrocio tra le due strade era parzialmente occupato da un ampio stagno poco profondo, che credo sia da tempo diventato terreno asciutto. La porta d'ingresso si apriva sulla strada, e una staccionata molto stretta da entrambe le parti proteggeva la casa dai possibili urti dei veicoli di passaggio. Un atrio di discrete dimensioni, e due salotti chiamati sala da pranzo e soggiorno, si estendevano per tutta la lunghezza della casa; tutte le stanze erano originariamente affacciate sulla strada, ma la grande finestra del soggiorno fu chiusa e trasformata in libreria quando Mrs. Austen ne prese possesso, e un'altra fu aperta di fianco, dalla quale si vedevano solo il prato e gli alberi; un alto recinto di legno la separava dalla strada (quella di Winchester) per tutta la lunghezza della piccola proprietà, e all'interno furono piantati degli alberi che formarono un boschetto dove passeggiare, che, correndo intorno al recinto, permetteva spazio sufficiente per fare esercizio fisico; non ci si doveva sentire rinchiusi in casa; e lì c'era un misto piacevole e irregolare di siepi, prato erboso, un vialetto di ghiaia, erba alta da tagliare, e il frutteto, che immagino era stato ricavato da due o tre piccoli recinti messi insieme e sistemati al meglio per permettere alle signore di lavorarlo. C'erano inoltre un orto accanto alla cucina, un ampio cortile e diversi edifici annessi, non molto utilizzati; e tutta questa abbondanza di spazio era molto gradita ai bambini, e non ho dubbi che aggiungesse molto al piacere di una visita. Tutto, dentro e fuori, era ben tenuto; la casa era ben arredata, ed era nel complesso una sistemazione comoda e signorile, anche se credo che non fossero stati impiegati larghi mezzi per renderla così. La casa era fatta praticamente come lo erano generalmente le canoniche dell'epoca, e quasi richiamava lo stesso vecchio stile; i soffitti bassi e poco rifiniti, alcune stanze da letto molto piccole, nessuna molto grande, ma in numero sufficiente ad accogliere gli abitanti e diversi ospiti. La sala da pranzo non poteva affacciarsi se non sulla strada, e lì mia nonna si sedeva spesso al mattino per un'ora o due, con il lavoro di cucito o a scrivere, godendosi l'aspetto luminoso e la scena movimentata che permetteva di vedere. Credo che l'estrema vicinanza della strada per lei non fosse in realtà un male più di quanto non lo fosse per i suoi nipoti. La diligenza giornaliera di Collyer a sei cavalli era uno spettacolo! (6) e ancora più bello per i bambini era sentire il terribile silenzio della notte rotto così di frequente dal passaggio di carrozze, che talvolta sembravano persino scuotere il letto. Il villaggio di Chawton è naturalmente da tempo più tranquillo, non è più un'importante via di transito, e ha subito altri e numerosi cambiamenti; e se qualcuno dei suoi visitatori non dovesse riconoscere dalla mia descrizione la casa e lo stagno, devo pregarli di non affrettarsi ad accusarmi di aver esagerato nel considerarlo così piacevole in passato. Vent'anni fa, quando il cottage rimase libero dopo la morte di mia zia Cassandra, (7) fu suddiviso in abitazioni per i poveri, in grado di accogliere diverse famiglie; così mi è stato detto, poiché da allora non l'ho più visto e credo che gli alberi siano stati tagliati, e tutto quello che poteva essere chiamato giardino sia stato di nuovo riportato a usi più comuni. Le mie visite a Chawton erano frequenti; non so dire quando iniziarono; a me faceva molto piacere andarci, e zia Jane era l'attrazione principale. Quando ero molto piccola, stavo sempre attaccata a lei, e la seguivo ovunque fosse possibile, in casa e fuori. Non posso ricordarmelo, ma da quanto mi diceva mia madre, non ero affatto un fastidio per mia zia. Il suo fascino nei confronti dei bambini era dovuto alla grande dolcezza dei modi; si vedeva che ti amava, e tu naturalmente in cambio la amavi. Questo, per quanto io possa ricordare e analizzare adesso, era ciò che provavo nella mia infanzia, prima di crescere abbastanza da apprezzare la sua intelligenza. Ma presto giunse la gioia della sua voce giocosa. Faceva di tutto per divertire un bambino. A quei tempi, mentre mi facevo più grande, e quando i miei cugini venivano a condividere il divertimento, ci raccontava le storie più deliziose, principalmente del regno delle fate, e le sue fate avevano tutte le caratteristiche che le contraddistinguono. Le storie erano, ne sono certa, inventate al momento, e talvolta andavano avanti per due o tre giorni, se l'occasione lo permetteva. Quanto all'aspetto di mia zia, il suo è il primo viso grazioso che mi ricordi, non che all'epoca usassi questa parola, ma so che la guardavo con ammirazione. Il suo viso era più rotondo che allungato, aveva un colorito luminoso, ma non roseo, una carnagione scura e trasparente e bellissimi occhi color nocciola. Non credo che fosse un'assoluta bellezza, ma prima che lasciasse Steventon era ritenuta una ragazza molto carina dalla maggior parte dei vicini, come ho appreso in seguito da alcuni di quelli che ancora restano. I capelli, di un castano scuro, erano ricci in modo naturale, con dei riccioli intorno al viso (poiché a quei tempi i cerchietti non c'erano). Portava sempre una cuffia. Così usavano fare le signore non più giovani, almeno al mattino, ma io non l'ho mai vista senza, per quanto possa ricordarmi, né di mattina né di sera. Credo che le mie zie non fossero reputate molto eleganti nel vestire, e si riteneva che avessero adottato troppo presto un abbigliamento da donne di mezza età; ma erano particolarmente curate, e ritenevano molto inappropriata la trascuratezza. Delle due, zia Jane era di gran lunga la mia prediletta. Non è che non mi piacesse la zia Cassandra, ma se per caso la mia visita fosse capitata durante la sua assenza, non penso che mi sarebbe mancata, mentre non trovare zia Jane a Chawton sarebbe stata davvero una disdetta. Man mano che crescevo, da mia nonna incontravo compagnia della mia età. Delle figlie del cap. Charles Austen, orfane di madre, (8) una, la primogenita, Cassy, visse lì per qualche tempo, seguita particolarmente da zia Cassandra; in seguito Chawton House fu per un periodo abitata dal cap. Frank Austen, e lui aveva molti figli. (9) Credo che fossimo tutti, in relazione alle nostre rispettive età e caratteri, molto affezionati a zia Jane, e che conserveremo sempre con forza il ricordo della piacevole vita di Chawton. Uno dei miei cugini, ora morto da tempo, (10) era solito, da grande, andarci di tanto in tanto a far visita a zia Cass., all'epoca l'unica rimasta nella vecchia casa, e una volta mi disse che per lui quelle visite erano sempre una delusione, poiché non poteva fare a meno di aspettarsi di sentirsi particolarmente felice a Chawton, e mai come quando ci arrivava era in grado di rendersi conto pienamente di come tutti i suoi peculiari piaceri fossero spariti. Al tempo della mia infanzia era una casa allegra; i miei zii, uno o l'altro, venivano di frequente per qualche giorno, e a tutti loro faceva piacere stare in famiglia; da allora, dopo aver conosciuto più di un focolare domestico, ho pensato che lo fosse in modo straordinario, dato che le chiacchiere familiari avevano sempre spirito e vivacità, e non erano mai turbate da disaccordi, perché non era loro abitudine litigare l'uno con l'altro. C'era sempre una perfetta armonia tra fratelli e sorelle, e sulla porta di mia nonna avrebbe potuto essere incisa la frase, "Ecco quanto è buono e quanto è soave che i fratelli vivano insieme." (11) C'era una salda unione familiare, mai spezzata se non dalla morte, anche se venne il tempo in cui quell'unione non avrebbe potuto essere preservata se l'affetto non fosse stato sorretto da uno spirito di indulgenza e generosità. (12) Zia Jane cominciava la giornata con la musica, per la quale sono convinta che avesse un gusto innato, dato che ci si dedicava con continuità, anche se nessuno gliel'aveva mai insegnata; non si lasciò mai convincere (da quello che so) a suonare in pubblico, e nessuno della famiglia se ne interessava molto. Immagino che fosse per non disturbarli, che preferisse esercitarsi prima della colazione, quando poteva avere la stanza tutta per sé. Si esercitava regolarmente ogni mattina. Suonava pezzi molto carini, così ritenevo, e mi piaceva stare accanto a lei ad ascoltarli; ma erano musiche (perché negli anni successivi conobbi bene quegli spartiti) che ora sarebbero considerate vergognosamente facili. Molto di quello che suonava era da manoscritti, copiati da lei stessa, e così puliti e corretti che si leggevano bene come se fossero stampati. Alle nove preparava la colazione, era quella la sua parte di faccende domestiche. La provvista di tè e zucchero, era compito suo, oltre al vino. Tutto il resto lo faceva zia Cassandra, poiché mia nonna aveva accettato di essere rimpiazzata dalle figlie prima di quanto io possa ricordare; e subito dopo, smise persino di sedersi a capotavola. Non credo che zia Jane usasse un metodo particolare per dividere la sua giornata, ma penso che in genere rimanesse in soggiorno fino al pranzo; e quando c'erano ospiti rimaneva lì, dedicandosi principalmente ai lavori di cucito. Amava cucire, ed era una grande esperta di ricamo e punto a croce, le cose preferite a quel tempo. La destrezza e l'ordine erano tra le sue caratteristiche. Sapeva lanciare i bastoncini di sciangai per noi meglio di chiunque altro, ed era straordinariamente brava a volano. Talvolta cercava sollievo in questo semplice gioco, quando soffriva di debolezza agli occhi e non poteva né cucire né leggere a lungo. La sua calligrafia resta a testimoniarne l'eccellenza; e ogni suo biglietto o lettera era scritto in modo splendido. A quel tempo ripiegare e sigillare le lettere era un'arte, non c'erano buste da incollare per rendere tutto più facile; le lettere di alcuni apparivano sempre fissate male e sciatte, ma i suoi fogli erano certi di prendere la giusta piega, e la sua ceralacca di cadere nel punto giusto. Dopo il pranzo, generalmente le mie zie uscivano; talvolta andavano ad Alton a fare spese, spesso una o l'altra a far visita alla Great House, com'era chiamata allora, quando c'era uno dei fratelli, oppure, se la casa era vuota, amavano gironzolare nei paraggi, qualche volta a Chawton Park, un bellissimo bosco di faggi raggiungibile con una passeggiata; ma talvolta, anche se succedeva raramente, a far visita a un vicino. Non avevano una carrozza, e nelle loro visite non si spingevano lontano; nel villaggio vivevano pochi gruppi familiari, ma con nessuno di loro si era instaurata una grande intimità; erano in rapporti di amicizia con tutti, ma in termini piuttosto distanti. Eppure sono certa che mia zia Jane avesse rispetto per i suoi vicini e provasse un benevolo interesse per ciò che succedeva loro. Le piaceva immensamente essere messa al corrente di tutto. Talvolta la facevano divertire, ma era il suo gusto per l'assurdo che dava sapore ai pettegolezzi. Non li metteva mai in ridicolo; era lontanissima dall'essere critica o mordace, non li offendeva o derideva. Questa era la parola usata a quel tempo, una brutta parola, ora obsoleta, e la brutta pratica che rivelava è ora molto meno diffusa, con qualsiasi nome, di quanto lo fosse allora. (13) Il riso che talvolta suscitava era dovuto all'immaginare per i suoi vicini delle circostanze improbabili, a raccontare, in prosa o in versi, qualche banale episodio ravvivato dalla sua fantasia, o a scrivere una storia su ciò che avevano detto o fatto, una storia che non poteva ingannare nessuno. Come esempio, vorrei citare la sua descrizione dei passatempi di Miss Mills e Miss Yates, due signorine delle quali lei non sapeva quasi nulla; erano solo in visita da un vicino ma i loro nomi la invogliarono a scrivere dei versi, e così fece. È successo prima dei miei tempi. Mrs. Lefroy (14) conosce i versi meglio di me; credo che ne abbia una copia, e non proverò a citarli qui in modo imperfetto. All'incirca nello stesso periodo (o almeno sempre prima dei miei tempi) possono forse essere datati alcuni capitoli, di cui ho sentito parlare, di una storia comica, scritta da lei insieme a una delle sue nipoti, e, senza dubbio, su sua istigazione. Se mi ricordo bene, non aveva altra base del fatto di aver visto un vicino passare in carrozza, senza che avessero saputo in precedenza che fosse in procinto di partire (mi è stato detto in seguito che fu scritta interamente dalla nipote, solo con il suo aiuto). (15) Non vedevo spesso mia zia con un libro in mano, ma sono convinta che fosse amante della lettura, che leggesse, e che leggesse moltissimo. Ho dei dubbi sul fatto che si occupasse molto di poesia in generale, ma era una grande ammiratrice di Crabbe, (16) e di conseguenza provava molto interesse nello scoprire chi fosse. Altri scrittori contemporanei erano ben conosciuti, ma, essendo le sue origini oscure, il suo nome non era noto di per sé; tuttavia, dopo diligenti ricerche, fu in grado ben presto di informare il resto della famiglia che era titolare del beneficio ecclesiastico di Trowbridge, e che si era di recente sposato per la seconda volta. Un'ammiratrice molto fervente delle opere di mia zia, ma estranea all'Inghilterra, ha recentemente osservato che sarebbe stato molto interessante conoscere l'opinione di Miss Austen sui grandi eventi pubblici della sua epoca, un periodo, come lei giustamente osserva, di grandissimo interesse, poiché mia zia era una giovane donna, già in grado di riflettere, al tempo della rivoluzione francese. Il lungo e disastroso capitolo iniziato allora, fu chiuso dalla battaglia di Waterloo, due anni prima della sua morte; chiunque può naturalmente desiderare di sapere da quale parte stesse una mente come la sua nei grandi conflitti bellici e politici che turbarono così tanto l'Europa per più di vent'anni; eppure è una domanda che non si è mai affacciata alla mia mente, e sebbene io abbia ora ripercorso i miei passi in quella direzione, non ho trovato assolutamente nulla! Per quanto riguarda la politica, la famiglia era generalmente conservatrice, più propensa a dare per scontato che a discutere, dato che persino i miei zii ne parlavano raramente, e invano cerco di rammentare qualche parola o frase di zia Jane che facesse riferimento ad avvenimenti pubblici. Naturalmente doveva avere una qualche tendenza, ma posso solo immaginare in quale direzione fosse rivolta. Delle sue opinioni sulla storia sono in grado di ricordare al massimo questo: che era una fedelissima sostenitrice di Carlo I, e che aveva sempre incoraggiato la mia fiducia giovanile nella completa innocenza di Maria Stuarda riguardo a tutti i crimini dei quali la storia ha gravato la sua memoria. (17) Mia zia passava sicuramente molto tempo a scrivere; la sua scrivania era in soggiorno. Spesso la vedevo lì a scrivere lettere, e sono convinta che abbia scritto nello stesso modo molti dei suoi romanzi, seduta insieme alla famiglia, quando erano da sole; ma non ho mai visto nessun manoscritto di quel genere, mentre scriveva. Scriveva molto spesso ai fratelli, quando erano in mare, e scambiava lettere con molti altri della famiglia. Non c'è nulla, nelle lettere che ho visto, che possa suscitare l'attenzione del pubblico. Erano scritte benissimo, e dovevano essere di estremo interesse per chi le riceveva; ma riguardavano principalmente i dettagli di avvenimenti domestici e familiari, e lei raramente azzardava anche solo un'opinione, cosicché per gli estranei non possono essere lo specchio della sua mente, non devono immaginare di poterla conoscere meglio leggendole. Erano eccessivamente prudenti, per avere valore. Le sue lettere alla zia Cassandra (perché talvolta erano separate) credo proprio che fossero aperte e confidenziali. Mia zia le controllò e ne bruciò la maggior parte (così mi disse) due o tre anni prima della propria morte. Ne lasciò, o ne diede alcune come ricordo alle nipoti, ma di quelle che ho visto io diverse avevano parti tagliate. Zia Jane era così buona da scrivermi spesso, e nel rivolgersi a una bambina era perfetta. Quando ero a Chawton, se c'erano anche le mie cugine Mary Jane e Cassy (18), spesso per i nostri svaghi ci servivamo della zia Jane. Era lei l'unica a cui ci rivolgevamo sempre per un aiuto. Ci dava volentieri quello che volevamo dal suo guardaroba, e sempre lei era spesso disposta a recitare la parte di una divertente ospite nella nostra casa immaginaria. Riusciva a divertirci in vari modi; una volta me la ricordo in una conversazione in cui io e le mie due cugine ci immaginavamo, già grandi, il giorno dopo un ballo a Bath. Una volta cresciuta, mi parlava in modo più serio delle mie letture, e dei miei svaghi. Avevo cominciato presto a scrivere versi e storie, e mi dispiace pensare a quanto le ho dato fastidio facendogliele leggere. Era molto gentile quando me ne parlava, e aveva sempre qualche elogio da tributare, ma alla fine mi metteva in guardia dal passarci troppo tempo. Diceva... come lo ricordo bene! che sapeva come fosse divertente scrivere storie, e che lei non lo riteneva un male, anche se molti, ne era consapevole, la pensavano in modo diverso, ma che alla mia età non sarebbe stato un bene essere troppo presa dalla scrittura. Più tardi, dopo essere andata a Winchester, mi mandò un messaggio di questo tenore: che se avessi seguito il suo consiglio, avrei dovuto smettere di scrivere fino ai sedici anni, e che lei stessa aveva spesso desiderato di aver letto di più, e scritto di meno, quando aveva la mia stessa età. (19) Era ritenuta molto brava a leggere a voce alta. Io non l'ho sentita spesso, ma una volta la vidi prendere un volume di Evelina (20) e leggere qualche pagina su Mr. Smith e i Brangston, e pensai che fosse come una recita. Aveva una voce molto eloquente. Era questa l'opinione dei suoi contemporanei, e anche se allora non ci pensavo come a qualcosa di perfetto, e non l'ascoltavo facendoci troppo caso, non ho mai dimenticato il timbro della sua voce; riesco a ricordarlo persino adesso, e so che era molto piacevole. Ho già parlato dell'armonia familiare che c'era tra i figli di mia nonna. Zia Jane era una sorella molto affezionata a tutti i suoi fratelli. Uno in particolare era il suo orgoglio e la sua delizia, (21) ma di tutta la famiglia, la più vicina e la più cara per tutta la vita fu senza dubbio la sorella, la sua unica sorella. Zia Cassandra era più grande di tre o quattro anni, e l'abitudine a guardarla con ammirazione, cominciata nell'infanzia, sembrava fosse sempre continuata. Quando ero una bambina, mi diceva spesso, quando ce n'era l'occasione, che la zia Cassandra poteva insegnarmi tutto meglio di quanto potesse fare lei. Zia Cass. ne sapeva di più. Zia Cass. poteva dirmi meglio quello che avrei dovuto sapere. Tutto ciò lo accolsi sempre in rispettoso silenzio. Forse pensava che la mia mente avesse bisogno di essere rivolta in quella direzione, ma credo sinceramente che lei abbia davvero sempre ritenuto la sorella superiore a lei. Tra di loro ci fu sempre un affetto e una fiducia assoluti, e grande e duraturo fu il dolore della sopravvissuta quando avvenne la separazione definitiva. La vita di mia zia a Chawton, per quanto ne so, fu serena e piacevole; c'era poca varietà in essa, e non sono a conoscenza di nessuna particolare difficoltà, fino a quando la sua salute non venne meno. Di tanto in tanto si assentava, quasi sempre per stare con la famiglia di uno dei fratelli. Nell'autunno del 1815 era a Londra, con mio zio, Mr. Henry Austen, che allora abitava a Hans Place ed era vedovo. (22) Durante quella visita, lui fu colto da una leggera febbre e peggiorò talmente che si disperò per la sua vita, e la zia Cassandra e mio padre furono chiamati lì; per uno o due giorni ci si aspettava di ora in ora la sua morte, ma il decorso fu favorevole e lui iniziò a ristabilirsi. Mio padre allora tornò a casa. Zia Cass. rimase per quasi un mese, e zia Jane rimase alcune settimane in più, per assistere il convalescente. Fu durante questo soggiorno a Londra che un piccolo raggio del favore reale brillò su di lei. Aveva pubblicato i suoi primi romanzi con il forte desiderio di rimanere anonima, ma si rivelò impossibile mantenere un segreto che così tanti della famiglia conoscevano, e in quel periodo aveva abbandonato quel tentativo, e il suo nome era stato reso pubblico a sufficienza, anche se non fu mai inserito nel frontespizio. Due dei grandi medici del tempo avevano assistito mio zio durante la sua malattia. Non sono, dopo tutto questo tempo, sufficientemente sicura di chi fossero, tanto da fornire i loro nomi, ma uno di loro era molto vicino al Principe Reggente, (23) e, nel corso delle sue visite durante la convalescenza di mio zio, un giorno disse a mia zia che il principe era un grande ammiratore dei suoi romanzi, che li leggeva spesso, e ne aveva una copia in ogni sua residenza. Che lui, il medico, aveva detto a sua Altezza Reale che Miss Austen era in quei giorni a Londra, e che per espresso desiderio del principe, Mr. Clarke, il bibliotecario di Carlton House, le avrebbe presto fatto visita. Mr. Clarke andò, confermò quegli omaggi, e invitò mia zia ad andare a Carlton House, dicendo che il principe lo aveva incaricato di mostrarle la biblioteca, aggiungendo molte cortesie circa il piacere che sua A.R. aveva tratto dai suoi romanzi. Ne erano stati pubblicati tre. L'invito non poteva essere rifiutato, e mia zia andò, il giorno concordato, a Carlton House. Visitò la biblioteca e, credo, qualche altra sala, ma i particolari della sua visita, se mai li ho saputi, li ho ormai dimenticati; solo di una cosa mi ricordo bene, che nel corso di essa Mr. Clarke, parlando di nuovo dell'ammirazione del reggente per i suoi scritti, la informò di essere stato incaricato di dire che se Miss Austen avesse avuto qualche altro romanzo in uscita, sarebbe stata completamente libera di dedicarlo al principe. Mia zia fece i ringraziamenti del caso, ma non aveva intenzione di accettare l'onore che le era stato offerto, finché qualcuno dei suoi amici la avvertì che quel permesso doveva essere considerato un ordine. In quel periodo era in stampa Emma, e così una dedica di poche righe venne apposta al primo volume, e seguendo ancora le istruzioni dei beninformati, lei mandò a Carlton House una copia, splendidamente rilegata, che suppongo abbia provocato i debiti ringraziamenti da parte di Mr. Clarke. Subito dopo la visita, mia zia tornò a casa, dove la piccola avventura fu oggetto di conversazione e procurò un qualche divertimento. Nella primavera successiva Mr. Henry Austen si trasferì da Londra, e mia zia non ebbe più occasione di essere così vicina alla Corte, né cercò mai di riallacciare rapporti con il medico, il bibliotecario o il principe, e così finì questo piccolo sprazzo di Patrocinio Reale. Credo che la salute di zia Jane cominciò a declinare qualche tempo prima di quando si accorse di stare davvero male, anche se cominciò ad ammettere di sentirsi meno in grado di fare esercizio fisico. In una lettera a me scrisse: "Ho fatto una passeggiata sull'Asino e mi è piaciuta moltissimo, e devi cercare di procurarmi giornate tranquille e miti affinché io possa uscire quasi sempre; troppo vento non mi fa bene, dato che soffro ancora di reumatismi. In breve, al momento sono un ben misero tesoro. Voglio stare meglio per quando verrai a trovarci." (24) Era stato approntato un carretto trainato da un asino, per comodità di mia nonna, ma credo che lei lo usasse di rado, e zia Jane lo trovava utile per andare ad Alton, dove, per un periodo, prese casa il cap. Austen, dopo aver lasciato l'alloggio del fratello a Chawton. Nelle mie visite successive al Chawton Cottage, ricordo che zia Jane era solita stare spesso sdraiata dopo il pranzo. Anche mia nonna si metteva di frequente sul divano, a volte di pomeriggio, a volte di sera, non in un momento preciso della giornata. Per la sua età era in buona salute, e spesso lavorava per ore in giardino, e naturalmente dopo aveva voglia di riposare. C'era un solo divano nella stanza, e zia Jane si sdraiava su tre sedie che sistemava per sé. Credo che avesse un cuscino, ma non sembrava una sistemazione comoda. Lo chiamava il suo divano, e persino quando l'altro era libero non lo occupava mai. Sembrava voler far credere di preferire le sedie. Mi meravigliavo continuamente, poiché il vero divano era di frequente libero, eppure lei si sdraiava in quel modo così scomodo. Spesso le chiedevo come potevano piacerle di più le sedie, e immagino che la infastidii fino a farmi dire il motivo di quella scelta, ovvero che se avesse mai usato il divano, la nonna l'avrebbe lasciato libero per lei, e non ci si sarebbe sdraiata, come era solita fare, anche quando ne avesse avuto voglia. Nel maggio del 1816 le mie due zie andarono per alcune settimane a Cheltenham; sono in grado di essere certa di questa data, e di altri avvenimenti simili, da un vecchio diario in mio possesso. (25) A quei tempi andare dall'Hampshire al Gloucestershire era un viaggio, e la loro prima tappa fu Steventon. Restarono per un giorno, e lasciarono mia cugina Cassy da noi durante la loro assenza. Stettero anche per breve tempo da Mr. Fowle a Kintbury, (26) credo che questo avvenne durante il viaggio di ritorno. Mrs. Dexter, all'epoca Mary Jane Fowle, mi disse in seguito che la zia Jane passò in rassegna i vecchi luoghi, e le vennero in mente vecchi ricordi associati a essi, in un modo molto particolare; li guardava, pensò mia cugina, come se non si aspettasse di rivederli. La famiglia di Kintbury, durante quella visita, ebbe l'impressione che la sua salute fosse in declino, anche se non sapevano di nessuna malattia specifica. L'anno 1817, l'ultimo della vita di mia zia, sembrò iniziare sotto migliori auspici. Trascrivo da una sua lettera a me datata 23 gennaio 1817, la sola lettera che ho dove è indicato l'anno. "Io mi sento più forte di quanto non fossi, e sono così perfettamente in grado di camminare fino a Alton, oppure di tornare indietro, senza la minima fatica che spero di poter fare entrambe le cose una volta arrivata l'estate." (27) Non so quando iniziarono gli allarmanti sintomi della sua malattia. Fu nel mese di marzo che capii per la prima volta come fosse malata seriamente. Era stato stabilito che all'incirca alla fine di quel mese, o all'inizio di aprile, avrei passato qualche giorno a Chawton, in assenza di mio padre e mia madre, che erano impegnati con Mrs. Leigh Perrot per sistemare gli affari del defunto marito - Mr. Leigh Perrot era morto da poco (28) - ma la zia Jane stava troppo male per farmi stare in casa loro, e così andai da mia sorella, Mrs. Lefroy, a Wyards. Il giorno dopo andammo a piedi a Chawton per chiedere notizie della zia. Era rinchiusa in camera sua ma disse che ci avrebbe visto volentieri, e andammo da lei. Era in vestaglia ed era seduta in poltrona proprio come un'invalida, ma si alzò e ci salutò con molta gentilezza, e poi, indicando le sedie che erano state sistemate per noi accanto al fuoco, disse, "C'è una sedia per la signora sposata, e uno sgabellino per te, Caroline." È strano, ma queste parole scherzose sono le ultime che ricordo di lei, perché non ho serbato memoria di nulla di ciò che fu detto nella conversazione che naturalmente seguì. Ero rimasta colpita dal cambiamento che c'era stato in lei. Era molto pallida, la voce era debole e bassa, e sembrava debilitata e sofferente; ma mi è stato detto che non ebbe mai dei veri dolori. Non era in grado di fare lo sforzo di chiacchierare con noi, e la nostra visita nella stanza della malata fu molto breve. La zia Cassandra ci fece presto andar via. Credo che non restammo per più di un quarto d'ora, e non rividi più la zia Jane. Credo che quel giorno stesse particolarmente male, e che in qualche modo in seguito si sia ripresa. Subito dopo tornai a casa, ma so che Mrs. Lefroy la vide più di una volta prima che andasse a Winchester. Fu durante il successivo mese di maggio che si trasferì là. C'era bisogno di consultare un medico migliore di quanto si potesse fare ad Alton. Non perché ci fossero molte speranze che una maggiore esperienza potesse garantire una cura, ma per il naturale desiderio della famiglia di metterla nelle mani migliori. Mr. Lyford era ritenuto molto bravo, tanto da essere generalmente chiamato anche da molto lontano, per fornire la sua opinione in caso di gravi malattie. Nelle fasi iniziali della sua malattia, mia zia si era avvalsa della consulenza, a Londra, di uno dei più eminenti medici dell'epoca. (29) Zia Cassandra, naturalmente, accompagnò la sorella e presero alloggio a College Street. Le loro grandi amiche Mrs. Heathcote e Miss Bigg, che allora vivevano vicino alla cattedrale, avevano preso gli accordi per conto loro, e fecero tutto ciò era in loro potere per favorirne le comodità durante il triste soggiorno a Winchester. Mr. Lyford non poté dare speranze di guarigione. Disse a mia madre che la durata della malattia era molto incerta, avrebbe potuto avere un decorso lento o, con le stesse probabilità, concludersi improvvisamente, e che temeva che il periodo finale, in qualsiasi momento fosse arrivato, avrebbe comportato molte sofferenze, ma questo fu misericordiosamente evitato. Mia madre, dopo un breve periodo, aveva raggiunto la cognata, per farle stare più serene, e anche per prendere parte alla necessaria assistenza. Da lei, quindi, ho appreso che la rassegnazione e la compostezza di mia zia furono tali da andare al di là di quanto si fossero aspettati quelli che la conoscevano bene. Era una cristiana umile e con molta fede; la sua vita era trascorsa nel gioioso adempimento di tutti i lavori domestici, e con nessuna aspirazione al plauso; aveva cercato come per istinto di promuovere la felicità di tutti coloro che erano intorno a lei, e senza dubbio ebbe la sua ricompensa nella serenità che le fu concessa nel suoi ultimi giorni. Era perfettamente consapevole del pericolo che correva, non erano le speranze illusorie a tenerla su di morale, e c'era tutto ciò che poteva farla sentire attaccata alla vita. Anche se era passata attraverso le speranze e le gioie della gioventù, si era lasciata alle spalle i dolori di quella fase della vita, e l'autunno è talvolta così tranquillo e bello che ci consola per il distacco dalla primavera e dell'estate, e così forse è stato per lei. Era stata felice nella sua famiglia e nella sua casa, e senza dubbio aver esercitato il suo grande talento era stata una felicità di per sé, e stava giusto imparando a prendere confidenza con il suo successo. In nessun animo umano c'era meno vanità che nel suo, anche se non poteva non sentirsi compiaciuta e gratificata che le sue opere si stessero lentamente facendo strada nel mondo, con un favore che cresceva in modo costante. Non aveva nessun motivo per essere stanca della vita, e ce n'erano molti che gliela rendevano molto piacevole. Possiamo essere certi che avrebbe volentieri continuato la sua vita, anche se era pronta, senza lamentarsi e senza paura, a prepararsi alla morte. Per qualche tempo era stata consapevole che avrebbe potuto approssimarsi a lei, e ormai sapeva con certezza di come fosse vicinissima. Durante le ultime fasi della sua malattia le vennero forniti i conforti religiosi adeguati al suo stato, talvolta da un fratello. Due di loro erano ecclesiastici e a Winchester era a poca distanza da entrambi. (30) La dolcezza del suo carattere non l'abbandonò mai; fu premurosa e grata con coloro che l'assistevano, e a volte, quando si sentiva un po' meglio, riemergeva il suo spirito giocoso, e riusciva a farli divertiva persino nella loro tristezza. Spesso uno dei fratelli passava per qualche ora, o per uno o due giorni. Improvvisamente si aggravò. Mr. Lyford riteneva che la fine fosse imminente, e lei stessa sapeva di stare per morire, e con questa certezza disse tutto ciò che desiderava dire a quelli che le stavano vicini. Nel prendere quello che lei riteneva fosse l'ultimo congedo da mia madre, la ringraziò per essere lì, e disse, "Sei sempre stata una sorella per me, Mary." Contrariamente a ogni aspettativa, il pericolo immediato si dileguò; divenne di nuovo serena, e sembrò davvero stare meglio. Mia madre allora tornò a casa, ma non per molto, dato che fu richiamata subito dopo, non per un peggioramento della malattia di mia zia, ma perché non si poteva avere più fiducia nell'infermiera per la sua parte di assistenza notturna, essendo stata più di una volta trovata addormentata; così, per sollevarla da quella parte dei suoi compiti, zia Cassandra, mia madre e la cameriera di mia zia si divisero le notti tra di loro. Zia Jane continuava ad essere allegra e serena, e cominciò a esserci una speranza che la morte si fosse per lo meno allontanata. Ma presto, e all'improvviso, ci fu un grande cambiamento; senza apparentemente molte sofferenze, declinò rapidamente. Mr. Lyford, quando la vide, non poté dare ulteriori speranze, e lei deve aver percepito il suo stato, poiché quando lui le chiese se volesse qualcosa, lei rispose, "Nulla se non la morte." Queste furono le sue ultime parole. La vegliarono tutta la notte, e tranquilla e in pace esalò l'ultimo respiro la mattina del 18 luglio 1817. Non ho certo bisogno di dire quanto fosse teneramente amata dalla sua famiglia. I fratelli erano molto fieri di lei. La sua fama letteraria, alla fine della sua vita, si stava appena diffondendo, ma erano fieri del suo talento, che essi persino allora stimavano molto, fieri delle sue virtù domestiche, del suo spirito allegro, del suo bell'aspetto, e tutti amavano in seguito immaginare una somiglianza in qualcuna delle loro figlie con la cara "zia Jane", della quale comunque non si aspettavano di trovare l'eguale. Marzo 1867 - Scritto