|

The Novels of Jane Austen

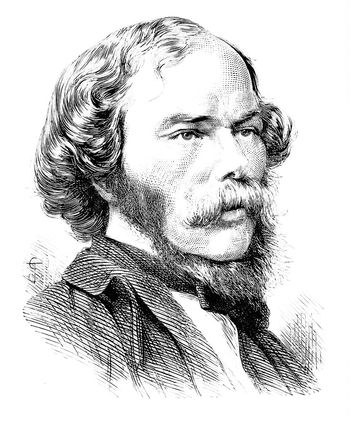

by George Henry Lewes

(1859)

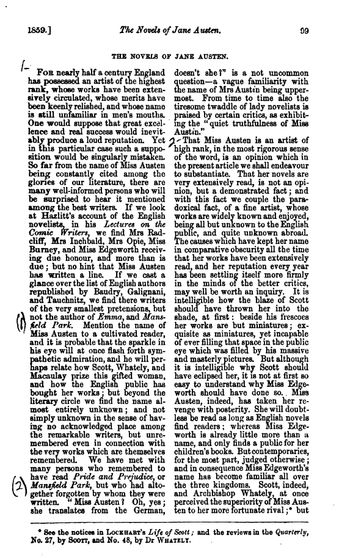

For nearly half a century England has possessed an artist of the highest rank, whose works have been extensively circulated, whose merits have been keenly relished, and whose name is still unfamiliar in men's mouths. One would suppose that great excellence and real success would inevitably produce a loud reputation. Yet in this particular case such a supposition would be singularly mistaken. So far from the name of Miss Austen being constantly cited among the glories of our literature, there are many well-informed persons who will be surprised to hear it mentioned among the best writers. If we look at Hazlitt's account of the English novelists, in his Lectures on the Comic Writers, we find Mrs Radcliff, Mrs Inchbald, Mrs Opie, Miss Burney, and Miss Edgeworth receiving due honour, and more than is due; but no hint that Miss Austen has written a line. If we cast a glance over the list of English authors republished by Baudry, Galignani, and Tauchnitz, we find there writers of the very smallest pretensions, but not the author of Emma, and Mansfield Park. Mention the name of Miss Austen to a cultivate reader, and it is probable that the sparkle in his eye will at once flash forth sympathetic admiration, and he will perhaps relate how Scott, Whately, and Macaulay prize this gifted woman, and how the English public has bought her works; but beyond this literary circle we find the name almost entirely unknown; and not simply unknown in the sense of having no acknowledged place among the remarkable writers, but unremembered even in connections with the very works which are themselves remembered. We have met with many persons who remembered to have read Pride and Prejudice or Mansfield Park, but who had altogether forgotten by whom they were written. "Miss Austen? Oh, yes; she translates from the German, doesn't she?" is not an uncommon question—a vague familiarity with the name of Mrs Austin being uppermost. From time to time also the tiresome twaddle of lady novelists is praised by certain critics, as exhibiting the "quiet truthfulness of Miss Austin."

That Miss Austen is an artist of high rank, in the most rigorous sense of the word, is an opinion which in the present article we shall endeavour to substantiate. That her novels are very extensively read, is not an opinion, but a demonstrated fact; and with this fact we couple the paradoxical fact, of a fine artist, whose works are widely known and enjoyed, being all but unknown to the English public, and quite unknown abroad. The causes which have kept her name in comparative obscurity all the time that her works have ben extensively read, and her reputation every year has been settling itself more firmly in the minds of the better critics, may well be worth an inquiry. It is intelligible how the blaze of Scott should have thrown her into the shade, at first: beside his frescoes her works are but miniatures; exquisite as miniatures, yet incapable of ever filling that space in the public eye which was filled by his massive and masterly pictures. But although it is intelligible why Scott should have eclipsed her, it is not at first so easy to understand why Miss Edgeworth should have done so. Miss Austen, indeed, has taken her revenge with posterity. She will doubtless be read as long as English novels find readers; whereas Miss Edgeworth is already little more than a name, and only finds a public for her children's books. But contemporaries, for the most part, judged otherwise; and in consequence Miss Edgeworth's name has become familiar all over the three kingdoms. Scott, indeed, and Archbishop Whately, at once perceived the superiority of Miss Austen to her more fortunate rival; but the Quarterly tells us that "her fame has grown fastest since she died: there was no éclat about her first appearance: the public took time to make up its mind; and she, not having staked her hopes of happiness on success or failure, was content to wait for the decision of her claims. Those claims have been long established beyond a question; but the merit of first recognizing them belongs less to the reviewers than to the general readers." There is comfort in this for authors who see the applause of reviewers lavished on works of garish effect. Nothing that is really good can fail, at last, in securing its audience; and it is evident that Miss Austen's works must possess elements of indestructible excellence, since, although never "popular," she survives writers who were very popular; and forty years after her death, gains more recognition than she gained when alive. Those who, like ourselves, haven read and re-read her works several times, can understand this duration, and this increase of her fame. But the fact that her name is not even now a household word proves that her excellence must be of an unobtrusive kind, shunning the glare of popularity, not appealing to temporary tastes and vulgar sympathies, but demanding culture in its admirers. Johnson wittily says of somebody, "Sir, he managed to make himself public without making himself known." Miss Austen has made herself known without making herself public. There is no portrait of her in the shop windows; indeed, no portrait of her at all. But she is cherished in the memories of those whose memory is fame.

As one symptom of neglect we have to notice the scantiness of all biographical details about her. Of Miss Burney, who is no longer read, nor much worth reading, we have biography, and to spare. Of Miss Brontë, who, we fear, will soon cease to find readers, there is also ample biography; but of Miss Austen we have little information. In the first volume of the edition published by Mr Bentley (five charming volumes, to be had for fifteen shillings) there is a meagre notice, from which we draw the following details.

Jane Austen was born on the 16th December 1775, at Steventon in Hampshire. Her father was rector of the parish during forty years, and then quitted it for Bath. He was a scholar, and fond of general literature, and probably paid special attention to his daughter's culture. In Bath, Jane only lived four years; but that was enough, and more than enough, for her observing humour, as we see in Northanger Abbey. After the death of her father, she removed with her mother and sister to Southampton; and finally, in 1809, settled in the pleasant village of Chawton, in Hampshire, from whence she issued her novels. Some of these had been written long before, but were withheld, probably because of her great diffidence. She had a high standard of excellence, and knew how prone self-love is to sophisticate. So great was this distrust, that the charming novel, Northanger Abbey, although the first in point of time, did not appear in print until after her death; and this work, which the Quarterly Review pronounces the weakest of the series (a verdict only intelligible to us because in the same breath Persuasion is called the best!) is not only written with unflagging vivacity, but contains two characters no one else could have equalled—Henry Tilney and John Thorpe. Sense and Sensibility was the first to appear, and that was in 1811. She had laid aside a sum of money to meet what she expected would be her loss on that publication, and "could scarcely believe her great good fortune when it produced a clear profit of £150." Between 1811 and 1816 appeared her three chefs-d'œuvre—Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park and Emma. The applause these met with, gratified her, of course; but she steadily resisted every attempt to "make a lion of her," and never publicly avowed her authorship, although she spoke freely of it in private. Soon after the publication of Emma, symptoms of an incurable decline appeared. In the month of May, 1817, she was removed to Winchester, in order that constant medical advice might be secured. She seems to have suffered much, but suffered it with resignation. Her last words were, "I want nothing but death." This was on Friday, the 18th July, 1817; presently after she expired in the arms of her sister. Her body lies in Winchester Cathedral.

One might gather from her works that she was personally attractive, and we are told in the memoir that this was the case. "Her stature rather exceeded the middle height; her carriage and deportment were quiet but graceful; her features were separately good; their assemblage produced an unrivalled expression of that cheerfulness, sensibility, and benevolence which were her real characteristics; her complexion was of the finest texture—it might with truth be said that her eloquent blood spoke through her modest cheek; her voice was sweet; she delivered herself with fluency and precision; indeed, she was formed for elegant and rational society, excelling in conversation as much as in composition." We may picture her as something like her own sprightly, natural, but by no means perfect Elizabeth Bennett, in Pride and Prejudice, one of the few heroines one would seriously like to marry.

We have no means of ascertaining how many copies of these exquisite pictures of English life have been circulated, but we know that the number is very large. Twice or thrice have the railway editions been out of print; and Mr Bentley's edition is stereotyped. This success implies a hold on the Public, all the more certainly because the popularity is "not loud but deep." We have re-read them all four times; or rather, to speak more accurately, they have been read aloud to us, one after the other; and when it is considered what a severe test that is, how the reading aloud permits no skipping, no evasion of weariness, but brings both merits and defects into stronger relief by forcing the mind to dwell on them, there is surely something significant of genuine excellence when both reader and listener finish their fourth reading with increase of admiration. The test of reading aloud applied to Jane Eyre, which had only been read once before, very considerably modified our opinion of that remarkable work; and, to confess the truth, modified it so far that we feel as if we should never open the book again. The same test applied to such an old favourite as Tom Jones, was also much more damaging than we should have anticipated—bringing the defects and shortcomings of that much overrated work into very distinct prominence, and lessening our pleasure in its effective, but, on the whole, coarse painting. Fielding has greater vigour of mind, greater experience, greater attainments, and a more effective mise en scène, than Miss Austen; but he is not only immeasurably inferior to her in the highest department of art—the representation of character—he is also inferior to her, we think, in real humour; and in spite of his "construction," of which the critics justly speak in praise, he is inferior to her in the construction and conduct of his story, being more commonplace and less artistic. He has more invention of situation and more vigour, but less truth and subtlety. This is at any rate our individual judgment, which the reader is at liberty to modify as he pleases. In the course of the fifteen years which have elapsed since we first read Emma, and Mansfield Park, we have outlived many admirations, but have only learned to admire Miss Austen more; and as we are perfectly aware of why we so much admire her, we may endeavour to communicate these reasons to the reader.

If, as probably few will dispute, the art of the novelist be the representation of human life by means of a story; and if the truest representation, effected by the least expenditure of means, constitutes the highest claim of art, then we say that Miss Austen has carried the art to a point of excellence surpassing that reached by any of her rivals. Observe we say "the art;" we do not say that she equals many of them in the interest excited by the art; that is a separate question. It is probable, nay certain, that the interest excited by the Antigone is very inferior to that excited by Black-eyed Susan. It is probably that Uncle Tom and Dred surpassed in interest the Antiquary or Ivanhoe. It is probable that Jane Eyre produced a far greater excitement than the Vicar of Wakefield. But the critic justly disregards these fervid elements of immediate success, and fixes his attention mainly on the art which is of eternal substance. Miss Austen has nothing fervid in her works. She is not capable of producing a profound agitation in the mind. In many respects this is a limitation of her powers, a deduction from her claims. But while other writers have had more power over the emotions, more vivid imaginations, deeper sensibilities, deeper insight, and more of what is properly called invention, no novelist has approached her in what we may style the "economy of art," by which is meant the easy adaptation of means to ends, with no aid from extraneous or superfluous elements. Indeed, paradoxical as the juxtaposition of the names may perhaps appear to those who have not reflected much on this subject, we venture to say that the only names we can place above Miss Austen, in respect of this economy of art, are Sophocles and Molière (in Les Misanthrope). And if any one will examine the terms of the definition, he will perceive that almost all defects in works of art arise from neglect of this economy. When the end is the representation of human nature in its familiar aspects, moving amid every-day scenes, the means must likewise be furnished from every-day life: romance and improbabilities must be banished as rigorously as the grotesque exaggeration of peculiar characteristics, or the representation of abstract types. It is easy for an artist to choose a subject from every-day life, but it is not easy for him so to represent the characters and their actions that they shall be at once lifelike and interesting; accordingly, whenever ordinary people are introduced, they are either made to speak a language never spoken out of books, and to pursue conduct never observed in life; or else they are intolerably wearisome. But Miss Austen is like Shakespeare: she makes her very noodles inexhaustibly amusing, yet accurately real. We never tire of her characters. They become equal to actual experiences. They live with us, and form perpetual topics of comment. We have so personal a dislike to Mrs Elton and Mrs Norris, that it would gratify our savage feeling to hear of some calamity befalling them. We think of Mr Collins and John Thorpe with such a mixture of ludicrous enjoyment and angry contempt, that we alternately long and dread to make their personal acquaintance. The heroines—at least Elizabeth, Emma, and Catherine Morland—are truly lovable, flesh-and-blood young women; and the good people are all really good, without being goody. Her reverend critic in the Quarterly says, "She herself compares her productions to a little bit of ivory, two inches wide, worked upon with a brush so fine that little effect is produced with much labour. It is so: her portraits are perfect likenesses, admirably finished, many of them gems; but it is all miniature-painting; and having satisfied herself with being inimitable in one line, she never essayed canvass and oils; never tried her hand at a majestic daub." This is very true: it at once defines her position and lowers her claims. When we said that in the highest department of the novelist's art—namely, the truthful representation of character—Miss Austen was without a superior, we ought to have added that in this department she did not choose the highest range; the truth and felicity of her delineations are exquisite, but the characters delineated are not of a high rank. She belongs to the great dramatists; but her dramas are of homely common quality. It is obvious that the nature of the thing represented will determine degrees in art. Raphael will always rank higher than Teniers; Sophocles and Shakespeare will never be lowered to the rank of Lope de Vega and Scribe. It is a greater effort of genius to produce a fine epic than a fine pastoral; a great drama than a perfect lyric. There is far greater stain on the intellectual effort to create a Brutus or an Othello, than to create a Vicar of Wakefield or a Squire Western. The higher the aims, the greater is the strain, and the nobler is success.

These, it may be said, are truism; and so they are. Yet they need restatement from time to time, because men constantly forget that the dignity of a high aim cannot shed lustre on an imperfect execution, though to some extent it may lessen the contempt which follows upon failure. It is only success which can claim applause. Any fool can select a great subject; and in general it is the tendency of fools to choose subjects which the strong feel to be too great. If a man can leap a five-barred gate, we applaud his agility; but if he attempt it, without a chance of success, the mud receives him, and we applaud the mud. This is too often forgotten by critics and artists, in their grandiloquence about "high art." No art can be high that is not good. A grand subject ceases to be grand when its treatment is feeble. It is a great mistake, as has been wittily said, "to fancy yourself a great painter because you paint with a big brush;" and there are unhappily too many big brushes in the hands of incompetence. Poor Haydon was a type of the big-brush school; he could not paint a small picture because he could not paint at all; and he believed that in covering a vast area of canvas he was working in the grand style. In every estimate of an artist's rank we necessarily take into account the nature of the subject and the excellence of the execution. It is twenty times more difficult to write a fine tragedy than a fine lyric; but it is more difficult to write a perfect lyric than a tolerable tragedy; and there was as much sense as sarcasm in Beranger's reply when the tragic poet Viennet visited him in prison, and suggested that of course there would be a volume of songs as the product of this leisure. "Do you suppose," said Beranger, "that chansons are written as easily as tragedies?"

To return to Miss Austen: her delineation is unsurpassed, but the characters delineated are never of a lofty or impassioned order, and therefore make no demand on the highest faculties of the intellect. Such genius as hers is excessively rare; but it is not the highest kind of genius. Murillo's peasant boys are assuredly of far greater excellence than the infant Christs painted by all other painters, except Raphael; but the divine children of the Madonna di San Sisto are immeasurably beyond any think Murillo has painted. Miss Austen's two-inch bit of ivory is worth a gallery of canvas by eminent R.A.'s, but it is only a bit of ivory after all. "Her two inches of ivory," continues the critic recently quoted, "just describes her preparations for a tale in three volumes. A village—two families connected together—three or four interlopers, out of whom are to spring a little tracasserie; and by means of village or country-town visiting and gossiping, a real plot shall thicken, and its "rear of darkness" never be scattered till six pages off finis. . . . .The work is all done by half-a-dozen people; no person, scene or sentence is ever introduced needless to the matter in hand: no catastrophes, or discoveries, or surprises of a grand nature are allowed—neither children nor fortunes are found or lost by accident—the mind is never taken off the level surface of life—the reader breakfasts, dines, walks, and gossips with the various worthies, till a process of transmutation takes place in him, and he absolutely fancies himself one of the company. . . . The secret is, Miss Austen was a thorough mistress in the knowledge of human character; how it is acted upon by education and circumstance, and how, when once formed, it shows itself through every hour of every day, and in every speech of every person. Her conversations would be tiresome but for this; and her personages, the fellows to whom may be met in the streets, or drank tea with at half an hour's notice, would excite no interest; but in Miss Austen's hands we see into their hearts and hopes, their motives, their struggles within themselves; and a sympathy is induced which, if extended to daily life and the world at large, would make the reader a more amiable person; and we must think it who does not close her pages with more charity in his heart towards unpretending, if prosing worth; with a higher estimation of simple kindness and sincere good-will; with a quickened sense of the duty of bearing and forbearing in domestic intercourse, and of the pleasure of adding to the little comforts even of persons who are neither wits nor beauties." It is worth remembering that this is the deliberate judgment of the present Archbishop of Dublin, and not a careless verdict dropping from the pen of a facile reviewer. There are two points in it to which especial attention may be given: first, The indication of Miss Austen's power of representing life; and, secondly, The indication of the effect which her sympathy with ordinary life produces. We shall touch on the latter point first; and we do so for the sake of introducing a striking passage from one of the works of Mr George Eliot, a writer who seems to us inferior to Miss Austen in the art of telling a story, and generally in what we have called the "economy of art;" but equal in truthfulness, dramatic ventriloquism, and humour, and greatly superior in culture, in reach of mind, and depth of emotional sensibility. In the first of the Scenes of Clerical Life there occurs this apology to the reader:—

"The Rev. Amos Barton, whose sad fortunes I have undertaken to relate, was, you perceive, in no respect an ideal or exceptional character, and perhaps I am doing a bold thing to bespeak your sympathy on behalf of a man who was so very far from remarkable,—a man whose virtues were not heroic, and who had no undetected crime within his breast; who had not the slightest mystery hanging about him, but was palpably and unmistakably common place; who was not even in love, but had had that complaint favorably many years ago. 'An utterly uninteresting character!' I think I hear a lady reader exclaim—Mrs. Farthingale, for example, who prefers the ideal in fiction; to whom tragedy means ermine tippets, adultery, and murder; and comedy, the adventures of some personage who is quite a 'character.'

"But, my dear madam, it is so very large a majority of your fellow-countrymen that are of this insignificant stamp. At least eighty out of a hundred of your adult male fellow-Britons returned in the last census, are neither extraordinarily silly, nor extraordinarily wicked, nor extraordinarily wise; their eyes are neither deep and liquid with sentiment; nor sparkling with suppressed witticisms; they have probably had no hairbreadth escapes or thrilling adventures; their rains are certainly not pregnant with genius, and their passions have not manifested themselves at all after the fashion of a volcano. They are simply men of complexions more or less muddy, whose conversation is more or less bald and disjointed. Yet these commonplace people—many of them—bear a conscience, and have felt the sublime prompting to do the painful right; they have their unspoken sorrows, and their sacred joys; their hearts have perhaps gone out towards their firstborn, and they have mourned over the irreclaimable dead Nay, is there not a pathos in their very insignificance; —in our comparison of their dim and narrow existence with the glorious possibilities of that human nature which they share?

"Depend upon it, you would gain unspeakably if you would learn with me to see some of the poetry and the pathos, the tragedy and the comedy, lying in the experience of a human soul that looks out through dull gray eyes, and that speaks in a voice of quite ordinary tones."

But the real secret of Miss Austen's success lies in her having the exquisite and rare gift of dramatic creation of character. Scott says of her, "She had a talent for describing the involvements, and feelings, and characters of ordinary life, which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with. The big bow-wow strain I can do myself like any one now going; but the exquisite touch, which renders ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting, from the truth of the description and the sentiment, is denied me. What a pity such a gifted creature died so early!" Generously said; but high as the praise is, it is as much below the real excellence of Miss Austen, as the "big bow-wow strain" is below the incomparable power of the Waverley Novels. Scott felt, but did not define, the excellence of Miss Austen. The very word "describing" is altogether misplaced and misleading. She seldom describes anything, and is not felicitous when she attempts it. But instead of description, the common and easy resource of novelists, she has the rare and difficult art of dramatic presentation: instead of telling us what her characters are, and what they feel, she presents the people, and they reveal themselves. In this she has never perhaps been surpassed, not even by Shakespeare himself. If ever living beings can be said to have moved across the page of fiction, as they lived, speaking as they spoke, and feeling as they felt, they do so in Pride and Prejudice, Emma, and Mansfield Park. What incomparable noodles she exhibits for our astonishment and laughter! What silly, good-natured women! What softly-selfish men! What lively, amiable, honest men and women, whom one would rejoice to have known!

But all her power is dramatic power; she loses her hold on us directly she ceases to speak through the personæ; she is then like a great actor off the stage. When she is making men and women her mouthpieces, she is exquisitely and inexhaustibly humorous; but when she speaks in her own person, she is apt to be commonplace, and even prosing. Her dramatic ventriloquism is such that, amid our tears of laughter and sympathetic exasperation at folly, we feel it almost impossible that she did not hear those very people utter those very words. In many cases this was doubtless the fact. The best invention does not consist in finding new language for characters, but in finding the true language for them. It is easy to invent a language never spoken by any one out of books; but it is so far from easy to invent—that is, to find out—the language which certain characters would speak and did speak, that in all the thousands of volumes written since Richardson and Fielding, every difficulty is more frequently overcome than that. If the reader fails to perceive the extraordinary merit of Miss Austen's representation of character, let him try himself to paint a portrait which shall be at once many-sided and interesting, without employing any but the commonest colours, without calling in the aid of eccentricity, exaggeration, or literary "effects;" or let him carefully compare the writings of Miss Austen with those of any other novelist, from Fielding to Thackeray.

It is probably this same dramatic instinct which makes the construction of her stories so admirable. And by construction, we mean the art which, selecting what is useful and rejecting what is superfluous, renders our interest unflagging, because one chapter evolves the next, one character is necessary to the elucidation of another. In what is commonly called "plot" she does not excel. Her invention is wholly in character and motive, not in situation. Her materials are of the commonest every-day occurrence. Neither the emotions of tragedy, nor the exaggerations of farce, seem to have the slightest attraction for her. The reader's pulse never throbs, his curiosity is never intense; but his interest never wanes for a moment. The action begins; the people speak, feel, and act; everything that is said, felt, or done tends towards the entanglement or disentanglement of the plot; and we are almost made actors as well as spectators of the little drama. One of the most difficult things in dramatic writing is so to construct the story that every scene shall advance the denouement by easy evolution, yet at the same time give scope to the full exhibition of the characters. In dramas, as in novels, we almost always see that the action stands still while the characters are being exhibited, and the characters are in abeyance while the action is being unfolded. For perfect specimens of this higher construction demanded by art, we would refer to the jealousy-scenes of Othello, and the great scene between Célimène and Arsinoé in Le Misanthrope; there is not in these two marvels of art a verse which does not exhibit some nuance of character, and thereby, at the same time, tends towards the full development of the action.

So entirely dramatic, and so little descriptive, is the genius of Miss Austen, that she seems to rely upon what her people say and do for the whole effect they are to produce on our imaginations. She no more thinks of describing the physical appearance of her people than the dramatist does who knows that his persons are to be represented by living actors. This is a defect and a mistake in art: a defect, because although every reader must necessarily conjure up to himself a vivid image of people whose characters are so vividly presented; yet each reader has to do this for himself without aid from the author, thereby missing many of the subtle connections between physical and mental organization. It is not enough to be told that a young gentleman had a fine countenance and an air of fashion; or that a young gentlewoman was handsome and elegant. As far as any direct information can be derived from the authoress, we might imagine that this was a purblind world, wherein nobody ever saw anybody, except in a dim vagueness which obscured all peculiarities. It is impossible that Mr Collins should not have been endowed by nature with an appearance in some way heralding the delicious folly of the inward man. Yet all we hear of this fatuous curate is, that "he was a tall, heavy-looking young man of five-and-twenty. His air was grave and stately, and his manners were very formal." Balzac or Dickens would not have been content without making the reader see this Mr. Collins. Miss Austen is content to make us know him, even to the very intricacies of his inward man. It is not stated whether she was shortsighted, but the absence of all sense of the outward world—either scenery or personal appearance—is more remarkable in her than in any writer we remember.

We are touching here on one of her defects which help to an explanation of her limited popularity, especially when coupled with her deficiencies in poetry and passion. She has little or no sympathy with what is picturesque and passionate. This prevents her from painting what the popular eye can see, and the popular heart can feel. The struggles, the ambitions, the errors, and the sins of energetic life are left untouched by her; and these form the subjects most stirring to the general sympathy. Other writers have wanted this element of popularity, but they have compensated for it by a keen sympathy with and power of representing, the adventurous, the romantic, and the picturesque. Passion and adventure are the sources of certain success with the mass of mankind. The passion may be coarsely felt, the romance may be ridiculous, but there will always be found a large majority whose sympathies will be awakened by even the coarsest daubs. Emotion is in its nature sympathetic and uncritical; a spark will ignite it. Types of villainy never seen or heard of out of books, or off the stage, types of heroism and virtue not less hyperbolical, are eagerly welcomed and believed in by a public which would pass over without notice the subtlest creations of genius, and which would even resent the more truthful painting as disturbing its emotional enjoyment of hating the bad, and loving the good. The nicer art which mingles goodness with villany, and weakness with virtue, as in life they are always mingled, causes positive distress to young and uncultivated minds. The mass of men never ask whether a character is true, or the events probable; it is enough for them that they are moved; and to move them strongly, black must be very black, and white without a shade. Hence it is that caricature and exaggeration of all kinds—inflated diction and daubing delineation—are, and always will be, popular: a certain breadth and massiveness of effect being necessary to produce a strong impression on all but a refined audience. In the works of the highest genius we sometimes find a breadth and massiveness of effect which make even these works popular, although the qualities most highly prized by the cultivated reader are little appreciated by the public. The Iliad, Shakespeare and Molière, Don Quixote and Faust, affect the mass powerfully; but how many admirers of Homer would prefer the naïveté of the original to the epigrammatic splendour of Pope?

The novelist who had no power of broad and massive effect can never expect to be successful with the great public. He may gain the suffrages of the highest minds, and in course of time become a classic; but we all know what the popularity of a classic means. Miss Austen is such a novelist. Her subjects have little intrinsic interest; it is only in their treatment that they become attractive; but treatment and art are not likely to captivate any except critical and refined tastes. Every reader will be amused by her pictures, because their very truth carries them home to ordinary experience and sympathy; but this amusement is of a tepid nature, and the effect is quickly forgotten. Partridge expressed the general sentiment of the public when he spoke slightingly of Garrick's Hamlet, because Garrick did just what he, Partridge, would have done in presence of a ghost; whereas the actor who performed the king, powerfully impressed him by sonorous elocution and emphatic gesticulation: that was acting, and required art; the other was natural, and not worth alluding to.

The absence of breadth, picturesqueness, and passion, will also limit the appreciating audience of Miss Austen to the small circle of cultivated minds; and even these minds are not always capable of greatly relishing her works. We have known very remarkable people who cared little for her pictures of every-day life; and indeed it may be anticipated that those who have little sense of humour, or whose passionate and insurgent activities demand in art a reflection of their own emotions and struggles, will find little pleasure in such homely comedies. Currer Bell may be taken as a type of these. She was utterly without a sense of humour, and was by nature fervid and impetuous. In a letter published in her memoirs she writes,—"Why do you like Miss Austen so very much? I am puzzled on that point. . . . I had not read Pride and Prejudice till I read that sentence of yours, and then I got the book. And what did I find? An accurate daguerreotyped portrait of a commonplace face; a carefully-fenced, highly-cultivated garden, with neat borders and delicate flowers; but no glance of a bright, vivid physiognomy, no open country, no fresh air, no blue hill, no bonny beck. I should hardly like to live with her elegant ladies and gentlemen, in their elegant but confined houses." The critical reader will not fail to remark the almost contemptuous indifference to the art of truthful portrait-painting which this passage indicates; and he will understand, perhaps, how the writer of such a passage was herself incapable of drawing more than characteristics, even in her most successful efforts. Jane Eyre, Rochester, and Paul Emmanuel, are very vigorous sketches, but the reader observes them from the outside, he does not penetrate their souls, he does not know them. What is said respecting the want of open country, blue hill, and bonny beck, is perfectly true; but the same point has been more felicitously touched by Scott in his review of Emma: "Upon the whole," he says, "the turn of this author's novels bears the same relation to that of the sentimental and romantic cast, that cornfields and cottages and meadows bear to the highly-adorned grounds of a show mansion or the rugged sublimities of a mountain landscape. It is neither so captivating as the one, nor so grand as the other; but it affords those who frequent it a pleasure nearly allied with the experience of their own social habits." Scott would also have loudly repudiated the notion of Miss Austen's characters being "mere daguerreotypes." Having himself drawn both ideal and real characters, he knew the difficulties of both; and he well says, "He who paints from le beau idéal, if his scenes and sentiments are striking and interesting, is in a great measure exempted from the difficult task of reconciling them with the ordinary probabilities of life; but he who paints a scene of common occurrence, places his composition within that extensive range of criticism which general experience offers to every reader. . . . Something more than a mere sign-post likeness is also demanded. The portrait must have spirit and character as well as resemblance; and being deprived of all that, according to Bayes, goes to 'elevate and surprise,' it must make amends by displaying depth of knowledge and dexterity of execution."

While defending our favourite, and giving critical reasons for our liking, we are far from wishing to impose that preference on others. If any one frankly says, "I do not care about these pictures of ordinary life: I want something poetical or romantic, something to stimulate my imagination, and to carry me beyond the circle of my daily thoughts,"—there is nothing to be answered. Many persons do not admire Wordsworth, and cannot feel their poetical sympathies aroused by waggoners and potters. There are many who find no enjoyment in the Flemish pictures, but are rapturous over the frescoes at Munich and Berlin. Individual tastes do not admit of dispute. The imagination is an imperious faculty, and demands gratification; and if a man be content to have this faculty stimulated, to the exclusion of all other faculties, or if only peculiar works are capable of stimulating it, we have no right to object. Only when a question of Art comes to be discussed, it must not be confounded with a matter of individual feeling; and it requires a distinct reference to absolute standards. The art of novel-writing, like the art of painting, is founded on general principles, which, because they have their psychological justification, because they are derived from tendencies of the human mind, and not, as absurdly supposed, derived from "models of composition," are of universal application. The law of colour, for instance, is derived from the observed relation between certain colours and the sensitive retina. The laws of construction, likewise, are derived from the invariable relation between a certain order and succession of events, and the amount of interest excited by that order. In novel-writing, as in mechanics, every obstruction is a loss of power; every superfluous page diminishes the artistic pleasures of the whole. Individual tastes will always differ; but the laws of the human mind are universal. One man will prefer the humorous, another the pathetic; one will delight in the adventurous, another in the simple and homely; but the principles of Art remain the same for each. To tell a story well, is quite another thing from having a good story to tell. The construction of a good drama is the same in principle whether the subject be Antigone, the Misanthrope, or Othello; and the real critic detects this principle at work under these various forms. It is the same with the delineation of character: however various the types, whether a Jonathan Oldbuck, a Dr. Primrose, a Blifil, or a Falstaff—ideal, or real, the principles of composition are the same.

Miss Austen has generally but an indifferent story to tell, but her art of telling it is incomparable. Her characters, never ideal, are not of an eminently attractive order; but her dramatic ventriloquism and power of presentation is little less than marvellous. Macaulay declares his opinion that in this respect she is second only to Shakespeare. "Among the writers," he says, "who, in the point we have noticed, have approached nearest the manner of the great master, we have no hesitation in placing Jane Austen, a woman of whom England is justly proud. She has given us a multitude of characters, all, in a certain sense, commonplace—all such as we meet every day. Yet they are all as perfectly discriminated from each other as if they were the most eccentric of human beings. . . . And all this is done by touches so delicate that they elude analysis, that they defy powers of description, and that we only know them to exist by the general effect to which they have contributed."

The art of the novelist consists in telling the story and representing the characters; but besides these, there are other powerful though extraneous sources of attraction often possessed by novels, which are due to the literary talent and culture of the writer. There is, for example, the power of description, both of scenery and of character. Many novels depend almost entirely on this for their effect. It is a lower kind of power, and consequently much more frequent than what we have styled the art of the novelist; yet it may be very puissant in the hands of a fine writer, gifted with a real sense of the picturesque. Being very easy, it has of late become the resource of weak writers; and the prominent position it has usurped has tended in two ways to produce weariness—first, by encouraging incompetent writers to do what is easily done; and, secondly, by seducing writers from the higher and better method of dramatic exposition.

Another source of attraction is the general vigour of mind exhibited by the author, in his comments on the incidents and characters of his story: these comments, when proceeding from a fine insight or a large experience, give additional charm to the story, and make the delightful novel a delightful book. It is almost superfluous to add, that this also has its obverse: the comments too often painfully exhibit a weakness of mind. Dr. Johnson refused to take tea with some one because, as he said, "Sir, there is no vigour in his talk." This is the complaint which must be urged against the majority of novelists: they put too much water in their ink. And even when the talk is good, we must remember that it is, after all, only one of the side-dishes of the feast. All the literary and philosophic culture which an author can bring to bear upon his work will tend to give that work a higher value, but it will not really make it a better novel. To suppose that culture can replace invention, or literature do instead of character, is as erroneous as the suppose that archæological learning and scenical splendor can raise poor acting to the level of fine acting. Yet this is the common mistake of literary men. They are apt to believe that mere writing will weigh in the scale against artistic presentation; that comment will do duty for dramatic revelation; that analysing motives with philosophic skill will answer all the purpose of creation. But whoever looks closely into this matter will see that literature—that is, the writing of thinking and accomplished men—is excessively cheap, compared with the smallest amount of invention or creation; and it is cheap because more easy of production, and less potent in effect. This is apparently by no means the opinion of some recent critics, who evidently consider their own writing of more merit than humour and invention, and who are annoyed at the notion of "mere serialists," without "solid acquirements," being regarded all over Europe as our most distinguished authors. Yet it may be suggested that writing such as that of the critics in question can be purchased in abundance, whereas humour and invention are among the rarest of products. If it is a painful reflection that genius should be esteemed more highly than solid acquirements, it should be remembered that learning is only the diffused form of what was once invention. "Solid acquirement" is the genius of wits, which has become the wisdom of reviewers.

Be this as it may, we acknowledge the great attractions which a novel may receive from the general vigor and culture of the author; and acknowledge that such attractions form but a very small element in Miss Austen's success. Her pages have no sudden illuminations. There are neither epigrams nor aphorisms, neither subtle analyses nor eloquent descriptions. She is without grace or felicity of expression; she has neither fervid nor philosophic content. Her charm lies solely in the art of representing life and character, and that is exquisite.

We have thus endeavoured to characterize, in general terms, the qualities which her works display. It is less easy to speak with sufficient distinctness of the particular works, since, unless our readers have these vividly present to memory (in which case our remarks would be superfluous), we cannot hope to be perfectly intelligible; no adequate idea of them can be given by a review of one, because the "specimen brick" which the noodle in Hierocles thought sufficient, and which really does suffice in the case of many a modern novel, would prove no specimen at all. Her characters are so gradually unfolded, their individuality reveals itself so naturally and easily in the course of what they say and do, that we learn to know them as if we had lived with them, but cannot by any single speech or act make them known to others. Aunt Norris, for instance, in Mansfield Park, is a character profoundly and variously delineated; yet there is no scene in which she exhibits herself to those who have not the pleasurable disgust of her acquaintance; while to those who have, there is no scene in which she does not exhibit herself. Mr Collins, making an offer to Elizabeth Bennet, formally stating the reasons which induced him to marry, and the prudential motives which have induced him to select her, and then adding, "Nothing now remains for me but to assure you, in the most animated language, of the violence of my affection. To fortune I am perfectly indifferent, and shall make no demand of that nature on your father, since I am well aware that it could not be complied with; and that one thousand pounds in the Four-per-Cents, which will not be yours till after your mother's decease, is all that you may ever be entitled to. On that head, therefore, I shall be uniformly silent; and you may assure yourself that no ungenerous reproach shall ever pass my lips when we are married;" and after her refusal, persisting in accepting this refusal as only what is usual with young ladies, who reject the addresses of the man they secretly mean to accept, "I am therefore by no means discouraged by what you have just said, and shall hope to lead you to the altar ere long;"—this scene, ludicrous as it is throughout, receives its exquisite flavour from what has gone before. We feel morally persuaded that so Mr Collins would speak and act. The man who, on taking leave of his host, formally assures him that he will not fail to send a "letter of thanks" on his return, and does send it, is just the man to have made this declaration. Mrs Elton, in Emma, is the very best portrait of a vulgar woman we ever saw: she is vulgar in soul, and the vulgarity is indicated by subtle yet unmistakable touches, never by coarse language, or by caricature of any kind. We will quote here a bit of her conversation in the first interview she has with Emma Woodhouse, in which she endeavours to be very fascinating. It should be premised that she is only just married, and this is the wedding-visit. She indulges in "raptures" about Hartfield (the seat of Emma's father), and Emma quietly replies:—

"'When you have seen more of this country, I am afraid you will think you have overrated Hartfield. Surrey is full of beauties.

"'Oh! yes, I am quite aware of that. It is the garden of England, you know, Surrey is the garden of England.'

"'Yes; but we must not rest our claims on that distinction. Many counties, I believe, are called the garden of England, as well as Surrey.'

"'No, I fancy not,' replied Mrs. Elton, with a most satisfied smile. 'I never heard any county but Surrey called so.'

"Emma was silenced.

"'My brother and sister have promised us a visit in the spring, or summer at farthest,' continued Mrs. Elton; 'and that will be our time for exploring. While they are with us, we shall explore a great deal, I dare say. They will have their barouche-landau, of course, which holds four perfectly; and therefore, without saying any thing of our carriage, we should be able to explore the different beauties extremely well. They would hardly come in their chaise, I think, at that season of the year. Indeed, when the time draws on, I shall decidedly recommend their bringing the barouche-landau; it will be so very much preferable. When people come into a beautiful country of this sort, you know, Miss Woodhouse, one naturally wishes them to see as much as possible; and Mr. Suckling is extremely fond of exploring. We explored to King's-Weston twice last summer, in that way, most delightfully, just after their first having the barouche-landau. You have many parties of that kind here, I suppose, Miss Woodhouse, every summer?'

"'No; not immediately here. We are rather out of distance of the very striking beauties which attract the sort of parties you speak of; and we are a very quiet set of people, I believe; more disposed to stay at home than engage in schemes of pleasure.'

"'Ah! there is nothing like staying at home for real comfort. Nobody can be more devoted to home than I am. I was quite a proverb for it at Maple Grove. Many a time has Selina said, when she has been going to Bristol, "I really cannot get this girl to move from the house. I absolutely must go in by myself, though I hate being stuck up in the barouche-landau without a companion; but Augusta, I believe, with her own good-will, would never stir beyond the park paling." Many a time has she said so; and yet I am no advocate for entire seclusion. I think, on the contrary, when people shut themselves up entirely from society, it is a very bad thing; and that it is much more advisable to mix in the world in a proper degree, without living in it either too much or too little. I perfectly understand your situation, however, Miss Woodhouse (looking towards Mr. Woodhouse). Your father's state of health must be a great drawback. Why does not he try Bath?—Indeed he should. Let me recommend Bath to you. I assure you I have no doubt of its doing Mr. Woodhouse good.'

"'My father tried it more than once, formerly; but without receiving any benefit; and Mr. Perry, whose name, I dare say, is not unknown to you, does not conceive it would be at all more likely to be useful now.'

"'Ah! that's a great pity; for I assure you, Miss Woodhouse, where the waters do agree, it is quite wonderful the relief they give. In my Bath life, I have seen such instances of it! And it is so cheerful a place, that it could not fail of being of use to Mr. Woodhouse's spirits, which, I understand, are sometimes much depressed. And as to its recommendations to you, I fancy I need not take much pains to dwell on them. The advantages of Bath to the young are pretty generally understood. It would be a charming introduction for you, who have lived so secluded a life; and I could immediately secure you some of the best society in the place. A line from me would bring you a little host of acquaintance; and my particular friend, Mrs. Partridge, the lady I have always resided with when in Bath, would be most happy to shew you any attentions, and would be the very person for you to go into public with.'

"It was as much as Emma could bear, without being impolite. The idea of her being indebted to Mrs. Elton for what was called an introduction—of her going into public under the auspices of a friend of Mrs. Elton's—probably some vulgar, dashing widow, who, with the help of a boarder, just made a shift to live!—The dignity of Miss Woodhouse, of Hartfield, was sunk indeed!

"She restrained herself, however, from any of the reproofs she could have given, and only thanked Mrs. Elton coolly; 'but their going to Bath was quite out of the question; and she was not perfectly convinced that the place might suit her better than her father.' And then, to prevent farther outrage and indignation, changed the subject directly.

"'I do not ask whether you are musical, Mrs. Elton. Upon these occasions, a lady's character generally precedes her; and Highbury has long known that you are a superior performer.'

"'Oh! no, indeed; I must protest against any such idea. A superior performer!—very far from it, I assure you. Consider from how partial a quarter your information came. I am doatingly fond of music—passionately fond; and my friends say I am not entirely devoid of taste; but as to any thing else, upon my honour my performance is médiocre to the last degree. You, Miss Woodhouse, I well know, play delightfully. I assure you it has been the greatest satisfaction, comfort, and delight to me, to hear what a musical society I am got into. I absolutely cannot do without music. It is a necessary of life to me; and having always been used to a very musical society, both at Maple Grove and in Bath, it would have been a most serious sacrifice. I honestly said as much to Mr. E. when he was speaking of my future home, and expressing his fears lest the retirement of it should be disagreeable; and the inferiority of the house too—knowing what I had been accustomed to—of course he was not wholly without apprehension. When he was speaking of it in that way, I honestly said that the world I could give up—parties, balls, plays—for I had no fear of retirement. Blessed with so many resources within myself, the world was not necessary to me. I could do very well without it. To those who had no resources it was a different thing; but my resources made me quite independent. And as to smaller-sized rooms than I had been used to, I really could not give it a thought. I hoped I was perfectly equal to any sacrifice of that description. Certainly I had been accustomed to every luxury at Maple Grove; but I did assure him that two carriages were not necessary to my happiness, nor were spacious apartments. "But," said I, "to be quite honest, I do not think I can live without something of a musical society. I condition for nothing else; but without music, life would be a blank to me.'"

"'We cannot suppose,' said Emma, smiling, 'that Mr. Elton would hesitate to assure you of there being a very musical society in Highbury; and I hope you will not find he has outstepped the truth more than may be pardoned, in consideration of the motive.'

"'No, indeed, I have no doubts at all on that head. I am delighted to find myself in such a circle; I hope we shall have many sweet little concerts together. I think, Miss Woodhouse, you and I must establish a musical club, and have regular weekly meetings at your house, or ours. Will not it be a good plan? If we exert ourselves, I think we shall not be long in want of allies. Something of that nature would be particularly desirable for me, as an inducement to keep me in practice; for married women, you know—there is a sad story against them, in general. They are but too apt to give up music.'

"'But you, who are so extremely fond of it—there can be no danger, surely?'

"'I should hope not; but really when I look around among my acquaintance, I tremble. Selina has entirely given up music; never touches the instrument, though she played sweetly. And the same may be said of Mrs. Jeffereys—Clara Partridge, that was—and of the two Milmans, now Mrs. Bird and Mrs. James Cooper; and of more than I can enumerate. Upon my word it is enough to put one in a fright. I used to be quite angry with Selina; but really I begin now to comprehend that a married woman has many things to call her attention. I believe I was half an hour this morning shut up with my housekeeper.'

"'But every thing of that kind,' said Emma, 'will soon be in so regular a train—'

"'Well,' said Mrs. Elton, laughing, 'we shall see.'"

Our limits force us to break off in the middle of this conversation, but the continuation is equally humorous. Quite as good in another way is Miss Bates with her affectionate twaddle. But, as we said before, the characters reveal themselves; and in general reveal themselves only in the course of several scenes, so that extracts would give no idea of them.

The reader who has yet to make acquaintance with these novels, is advised to begin with Pride and Prejudice or Mansfield Park; and if these do not captivate him, he may fairly leave the others unread. In Pride and Prejudice there is the best story, and the greatest variety of character: the whole Bennet family is inimitable: Mr Bennet, caustic, quietly, indolently selfish, but honourable, and in some respects amiable; his wife, the perfect type of a gossiping, weak-headed, fussy mother; Jane a sweet creature; Elizabeth a sprightly and fascinating flesh-and-blood heroine; Lydia a pretty, but vain and giddy girl; and Mary, plain and pedantic, studying "thorough bass and human nature." Then there is Mr Collins, and Sir William Lucas, and the proud, foolish old lady Catherine de Bourgh, and Darcy, Bingley, and Wickham, all admirable. From the first chapter to the last there is a succession of scenes of high comedy, and the interest is unflagging. Mansfield Park is also singularly fascinating, though the heroine is less of a favourite with us than Miss Austen's heroines usually are; but aunt Norris and Lady Bertram are perfect; and the scenes at Portsmouth, when Fanny Price visits her home after some years' residence at the Park, are wonderfully truthful and vivid. The private theatricals, too, are very amusing; and the day spent at the Rushworths' is a masterpiece of art. If the reader has really tasted the flavour of these works, he will need no other recommendation to read and re-read the others. Even Persuasion, which we cannot help regarding as the weakest, contains exquisite touches, and some characters no one else could have surpassed.

We have endeavoured to express the delight which Miss Austen's works have always given us, and to explain the sources of her success by indicating the qualities which make her a model worthy of the study of all who desire to understand the art of the novelist. But we have also indicated what seem to be the limitations of her genius, and to explain why it is that this genius, moving only amid the quiet scenes of every-day life, with no power over the more stormy and energetic activities which find vent even in every-day life, can never give her a high rank among great artists. Her place is among great artists, but it is not high among them. She sits in the House of Peers, but it is as a simple Baron. The delight derived from her pictures arises from our sympathy with ordinary characters, our relish of humour, and our intellectual pleasure in art for art's sake. But when it is admitted that she never stirs the deeper emotions, that she never fills the soul with a noble aspiration, or brightens it with a fine idea, but, at the utmost, only teaches us charity for the ordinary failings of ordinary people, and sympathy with their goodness, we have admitted an objection which lowers her claims to rank among the great benefactors of the race; and this sufficiently explains why, with all her excellence, her name has not become a household word. Her fame, we think, must endure. Such art as hers can never grow old, never be superseded. But, after all, miniatures are not frescoes, and her works are miniatures. Her place is among the Immortals; but the pedestal is erected in a quiet niche of the great temple.

|

I romanzi di Jane Austen

di George Henry Lewes

(1859)

Per quasi mezzo secolo l'Inghilterra ha avuto un'artista di altissimo livello, le cui opere sono ampiamente circolate, i cui meriti sono stati vivamente apprezzati, e il cui nome non è per nulla familiare. Si potrebbe supporre che una grande eccellenza e un concreto successo producano inevitabilmente una fama altisonante. Eppure in questo caso particolare una supposizione del genere sarebbe curiosamente sbagliata. Il nome di Miss Austen è ben lungi dall'essere costantemente citato tra le glorie della nostra letteratura, e ci sono molte persone ben informate che si sorprenderebbero nel sentirla menzionare tra i grandi romanzieri. Se guardiamo al resoconto di Hazlitt sui romanzieri inglesi, nel suo Lectures on the Comic Writers, scopriamo che Mrs. Radcliffe, Mrs Inchbald, Mrs Opie, Miss Burney e Miss Edgeworth sono citate con i dovuti onori, più di quanti ne siano dovuti, mentre non c'è nessun accenno nemmeno a un rigo di Miss Austen. Se diamo un'occhiata alla lista degli autori inglesi ristampata da Baudry, Galignani e Tauchnitz, ci troviamo scrittori di ben minori pretese, ma non l'autrice di Emma e Mansfield Park. Fate il nome di Miss Austen a un lettore abituale, ed è probabile che il suo sguardo brilli subito di ammirazione, e forse vi riferirà di come Scott, Whately e Macaulay apprezzino questa donna così dotata, e come il pubblico inglese abbia sempre comprato le sue opere; ma al di là di questa cerchia letteraria il suo nome è totalmente sconosciuto; e non semplicemente sconosciuto nel senso di non riconoscere che abbia un posto tra i grandi scrittori, ma mai rammentato persino in relazione a opere che invece sono impresse nella memoria. Abbiamo incontrato molte persone che ricordavano di aver letto Orgoglio e pregiudizio o Mansfield Park, ma che avevano del tutto dimenticato chi li avesse scritti. "Miss Austen? Oh, sì; traduce dal tedesco, no?" non è una domanda insolita, essendo prevalente una vaga familiarità con il nome di Miss Austin. Di tanto in tanto, anche le noiose inconcludenze di signore che scrivono romanzi sono elogiate da certi critici citando la "sobria veridicità di Miss Austin."

Che Miss Austen sia un'artista di alto livello, nel più rigoroso senso della parola, è l'opinione che il presente articolo cercherà di dimostrare. Che i suoi romanzi siano ampiamente letti non è un'opinione, ma un dato di fatto; e a questo fatto ne accoppiamo un altro paradossale, quello di una raffinata artista le cui opere sono largamente conosciute e godute, essendo quasi ignota al pubblico inglese e del tutto sconosciuta all'estero. Le cause che hanno tenuto il suo nome in relativa oscurità mentre le sue opere venivano ampiamente lette, e la sua fama si faceva di anno in anno più salda nelle menti dei critici migliori, sono degne di essere indagate. È comprensibile come il fulgore di Scott l'abbia messa inizialmente in ombra: di fronte ai suoi affreschi le opere di Miss Austen non sono che miniature; squisite come miniature, ma incapaci di riempire agli occhi del pubblico lo spazio colmato da immagini così imponenti e magistrali. Ma sebbene sia evidente il perché Scott l'abbia eclissata, non è così facile capire perché lo sia stata anche da Miss Edgeworth. Miss Austen, in effetti, si è presa la sua rivincita con i posteri. Senza dubbio sarà letta fino a quando i romanzi inglesi avranno un pubblico, laddove Miss Edgeworth è già diventata poco più di un nome, e trova un pubblico solo per i suoi libri per bambini. Ma i contemporanei, in larga parte, giudicavano altrimenti, e, di conseguenza, il nome di Miss Edgeworth è diventato familiare dappertutto nei tre regni. Scott e l'arcivescovo Whately, in verità, capirono subito la superiorità di Miss Austen sulla sua più fortunata rivale; (1) ma la Quarterly ci dice che "la sua fama è cresciuta molto rapidamente dopo la sua morte; non si rese manifesta fin dall'inizio; il pubblico si prese tempo per assimilarla; e lei, non avendo fondato le sue speranze di felicità sul successo o sul fallimento, si accontentò di aspettare gli sviluppi di quanto le era dovuto. E quanto le era dovuto è ormai stabilito al di là di ogni dubbio; ma il merito dei primi riconoscimenti è da attribuire più ai semplici lettori che ai critici letterari." (2) Queste parole sono un balsamo per quegli autori che vedono il plauso dei recensori sparso a piene mani su opere di maggiore effetto. Nulla di ciò che è realmente valido può, alla lunga, fallire dell'assicurarsi il proprio pubblico, ed è evidente come le opere di Miss Austen posseggano elementi di indubbia eccellenza, dato che, sebbene mai "popolare", è sopravvissuta a scrittori che erano molto popolari, e quarant'anni dopo la sua morte riceve più riconoscimenti di quanti ne abbia ottenuti in vita. Coloro che, come noi, hanno letto e riletto le sue opere diverse volte, riescono a comprendere questa durata e questo aumento della sua fama. Ma il fatto che il suo nome non sia finora diventato familiare dimostra come la sua eccellenza debba essere di un genere discreto, che elude il fulgore della popolarità, che non soddisfa appetiti provvisori e simpatie di bassa lega, ma richiede cultura ai suoi ammiratori. Johnson dice con arguzia di qualcuno, "Signore, lui è riuscito a farsi conoscere pubblicamente senza far conoscere se stesso." (3) Miss Austen si è fatta conoscere senza farsi conoscere pubblicamente. Non c'è nessun ritratto di lei nelle vetrine dei negozi; in effetti, non esiste affatto un suo ritratto. (4) Ma è serbata con cura tra le memorie di coloro la cui memoria è fama.

Come sintomo di questa trascuratezza, dobbiamo evidenziare la scarsezza di qualsiasi dettaglio biografico che la riguardi. Di Miss Burney, che ormai non è più letta, né molto meritevole di esser letta, abbiamo biografie a profusione. Anche di Miss Brontë, che temiamo cesserà presto di avere lettori, c'è un'estesa biografia; (5) ma su Miss Austen possediamo poche informazioni. Nel primo volume dell'edizione pubblicata da Mr. Bentley (cinque incantevoli volumi, che si possono comprare a quindici scellini) c'è una scarna nota biografica, (6) dalla quale traiamo i dettagli che seguono.

Jane Austen nacque il 16 dicembre 1775 a Steventon, nell'Hampshire. Il padre fu rettore della locale parrocchia per quarant'anni, e poi la lasciò per traferirsi a Bath. Era uno studioso, amante della letteratura, e probabilmente dedicò particolare attenzione all'istruzione della figlia. A Bath, Jane visse solo per quattro anni, ma quel periodo fu sufficiente, più che sufficiente, per il suo spirito d'osservazione, come possiamo vedere ne L'abbazia di Northanger. Dopo la morte del padre, si trasferì, con la madre e la sorella, a Southampton, e finalmente, nel 1809, si stabilì nel ridente villaggio di Chawton, nell'Hampshire, da dove pubblicò i suoi romanzi. Alcuni erano stati scritti molto tempo prima, ma tenuti nascosti, probabilmente a causa della sua grande modestia. Aveva modelli di valore molto alti, e sapeva quanto l'egocentrismo induca a sbagliare. La sua cautela era talmente grande, che l'incantevole romanzo L'abbazia di Northanger, sebbene cronologicamente il primo, non apparve che dopo la sua morte; e quest'opera, che la Quarterly Review giudica la più debole della serie (un giudizio per noi incomprensibile, visto che nello stesso tempo Persuasione è ritenuta la migliore!) (7) è non solo scritta con inesauribile vivacità, ma contiene due personaggi non eguagliati da nessun altro: Henry Tilney e John Thorpe. Ragione e sentimento fu la prima ad apparire, nel 1811. L'autrice aveva messo da parte una somma di denaro per far fronte a quello che si aspettava avrebbe perso con quella pubblicazione, e "Non riusciva quasi a credere alla sua grande buona sorte quando essa produsse un profitto netto di 150 sterline." (8) Tra il 1811 e il 1816 apparvero i suoi tre chefs-d'œuvre: Orgoglio e pregiudizio, Mansfield Park e Emma. Il plauso che ricevettero naturalmente fu gratificante per lei, che però resistette tenacemente a ogni tentativo di "metterla su un piedistallo", e non pubblicizzò mai la sua identità di autrice, anche se ne parlava liberamente in privato. Subito dopo la pubblicazione di Emma, apparvero i primi sintomi di una incurabile spossatezza. Nel mese di marzo del 1817 venne portata a Winchester, allo scopo di assicurarle la constante presenza di un medico. Soffrì molto, ma con rassegnazione. Le sue ultime parole furono, "Non desidero nulla se non la morte." (9) Avvenne venerdì 18 luglio 1817; subito dopo spirò tra le braccia della sorella. È sepolta nella cattedrale di Winchester.

Dalle sue opere si potrebbe dedurre che fosse fisicamente attraente, e dal Ricordo apprendiamo che era così. "La statura era superiore alla media; il portamento e il contegno erano tranquilli, ma aggraziati; i tratti del volto, presi separatamente, erano belli; messi insieme producevano un'ineguagliabile impressione di quell'allegria, sensibilità e bontà d'animo che erano le sue reali caratteristiche; la carnagione era finissima, si potrebbe davvero dire che l'eloquenza dell'animo si esprimeva attraverso la pudicizia della guancia; la voce era estremamente dolce; si esprimeva con scioltezza e precisione; era davvero fatta per la società elegante e razionale, per l'eccellenza della conversazione quanto della scrittura." Possiamo figurarcela come in qualche modo somigliante alla sua vivace, schietta ma non certo perfetta Elizabeth Bennet in Orgoglio e pregiudizio, una delle poche eroine che ciascuno di noi vorrebbe sposare.

Non abbiamo modo di accertare quante copie siano circolate di queste squisite descrizioni di vita inglese, ma sappiamo che il numero è cospicuo. Per due o tre volte le edizioni a prezzo minore sono andate esaurite, e per l'edizione di Mr Bentley è accaduto lo stesso. Questo successo indica una presa sul pubblico, tanto più che la sua popolarità non è "vistosa ma profonda". (10) L'abbiamo letta integralmente quattro volte, o piuttosto, per essere più accurati, abbiamo letto a noi stessi tutti i romanzi a voce alta, uno dopo l'altro; e se si considera che prova decisiva essa sia, come la lettura a voce alta non permetta salti e scappatoie, ma metta in forte rilievo pregi e difetti, costringendo la mente a indugiare su di essi, c'è sicuramente qualcosa di genuinamente eccellente dietro, quando sia il lettore che l'ascoltatore concludono la quarta lettura con crescente ammirazione. La prova della lettura a voce alta di Jane Eyre, letta una sola volta in precedenza, ha considerevolmente modificato la nostra opinione su questa notevole opera, e, a dire la verità, l'ha modificata così tanto che probabilmente non apriremo più il libro. La stessa prova, applicata a un vecchio classico come Tom Jones, è stata ancora più deleteria di quanto ci fossimo aspettati, facendo emergere chiaramente difetti e manchevolezze di quest'opera molto sopravvalutata, e facendo diminuire il nostro piacere, ancora d'effetto, ma, tutto sommato, di grana grossa. Fielding ha un animo più vigoroso, più esperienza, più risultati, e una mise en scène più d'effetto rispetto a Miss Austen; ma non le è solo incomparabilmente inferiore nelle alte sfere dell'arte - la raffigurazione dei personaggi - ma anche, riteniamo, nell'autentico umorismo; e nonostante la sua "costruzione" sia giustamente elogiata dai critici, le è inferiore nella costruzione e negli sviluppi della storia, più banali e meno artistici. Egli ha più inventiva e vigore nelle vicende che narra, ma meno veridicità e sottigliezza. Si tratta in ogni modo di un giudizio personale, che il lettore è libero di modificare a suo piacimento. Nei quindici anni trascorsi da quando abbiamo letto per la prima volta Emma e Mansfield Park, abbiamo superato molte predilezioni, ma abbiamo solo imparato ad amare di più Miss Austen, e dato che siamo perfettamente consapevoli del perché l'ammiriamo tanto, possiamo cercare di comunicarne le ragioni al lettore.

Se, come probabilmente pochi contesteranno, l'arte del romanziere è la rappresentazione della vita umana attraverso una storia, e se la rappresentazione più vera, realizzata con il minimo dispiego di mezzi, costituisce la massima pretesa di quest'arte, allora possiamo dire che Miss Austen ha portato l'arte a un punto di eccellenza che supera quanto raggiunto da tutti i suoi rivali. Si noti che diciamo "l'arte"; non diciamo che essa eguagli molti di loro nell'interesse suscitato dall'arte, il che è un'altra questione. È probabile, anzi certo, che l'interesse suscitato dall'Antigone sia molto inferiore a quello suscitato da Susan dagli occhi azzurri. (11) È probabile che Zio Tom e Dred (12) superino in interesse L'antiquario o Ivanhoe. È probabile che Jane Eyre produca di gran lunga più emozioni del Vicario di Wakefield. Ma la critica trascura giustamente gli elementi ardenti di successo immediato, e rivolge l'attenzione principalmente all'arte formata di sostanza eterna. Nelle opere di Miss Austen non c'è nulla di ardente. Non è capace di suscitare una profonda inquietudine. Per molti aspetti è un limite alle sue capacità, qualcosa che tende a diminuire quanto le è dovuto. Ma mentre altri scrittori hanno dimostrato maggiori capacità nel suscitare emozioni, un'immaginazione più viva, un'emotività più profonda, un più profondo intuito, e più di quella che è correttamente chiamata invenzione, nessun romanziere le si avvicina in ciò che possiamo denominare "l'economia dell'arte", ovvero un facile adattamento dei mezzi ai fini, con nessun ricorso a elementi estranei o superflui. In effetti, paradossalmente come la giustapposizione dei nomi può forse apparire a coloro che non hanno riflettuto abbastanza su questo argomento, ci azzardiamo ad affermare che i soli nomi che possiamo mettere al di sopra di Miss Austen, rispetto a questa economia dell'arte, sono quelli di Sofocle e di Molière (nel Misantropo). E chiunque esamini i termini della definizione, si renderà conto che quasi tutti i difetti nelle opere d'arte emergono dal trascurare questa economia. Quando il fine è la rappresentazione della natura umana nei suoi aspetti familiari, i mezzi devono allo stesso modo essere forniti dalla vita di tutti i giorni, muovendosi negli scenari di tutti i giorni; avventure fantastiche e avvenimenti improbabili devono essere banditi rigorosamente, così come le grottesche esagerazioni di caratteristiche particolari, o la raffigurazione di tipi astratti. È facile per un artista scegliere un argomento dalla vita di tutti i giorni, ma non è così facile descrivere i personaggi e le azioni che compiono facendo sì che siano allo stesso tempo realistici e interessanti; di conseguenza, ogni qualvolta vengano introdotte persone comuni, vengono fatte parlare con un linguaggio mai parlato al di fuori dei libri, e agire in modo mai osservato nella vita reale, altrimenti risulterebbero intollerabilmente noiose. Ma Miss Austen è come Shakespeare: sa rendere i suoi sciocchi invariabilmente divertenti, ma accuratamente reali. Non ci stanchiamo mai dei suoi personaggi. Diventano persone reali. Vivono con noi, e sono oggetto di continui commenti. Abbiamo un'antipatia così concreta verso Mrs Elton e Mrs Norris, che gratificherebbe i nostri sentimenti primigeni venire a sapere di una qualche calamità che le ha colpite. Pensiamo a Mr Collins e a John Thorpe con una tale mescolanza di comico piacere e irritato disprezzo, che di volta in volta la possibilità di conoscerli personalmente suscita in noi desiderio o spavento. Le eroine, perlomeno Elizabeth, Emma e Catherine Morland, sono davvero amabili giovinette in carne e ossa; e i buoni sono tutti realmente buoni, senza essere sdolcinati. Il rispettabile critico della Quarterly dice: "Lei stessa paragonò la sua produzione a un pezzettino di avorio, largo due pollici, lavorato con un pennello talmente fine da produrre un effetto minimo dopo tanta fatica. È proprio così: i suoi ritratti sono perfettamente somiglianti, elegantemente rifiniti, molti di loro delle gemme, ma sono tutte miniature, e, soddisfatta di essere ineguagliabile in quel tratteggio, non si cimentò mai con tela e olio, non mise mai mano a un maestoso affresco." (13) Questo è verissimo, definisce la sua collocazione e nello stesso tempo riduce quanto le è dovuto. Quando abbiamo affermato che nella sfera più alta dell'arte del romanziere - vale a dire la fedele rappresentazione dei personaggi - Miss Austen non aveva rivali, avremmo dovuto aggiungere che in quella sfera lei non scelse il livello più alto; la verità e l'efficacia delle sue raffigurazioni sono squisite, ma i personaggi raffigurati non sono di alto rango. Lei appartiene ai grandi drammaturghi, ma i suoi drammi sono di qualità comune, familiare. È ovvio che la natura delle cose rappresentate determinerà il livello dell'oggetto d'arte. Raffaello sarà sempre a un livello più alto di Teniers; Sofocle e Shakespeare non scenderanno mai al livello di Lope de Vega e di Scribe. Il cimento del genio sarà maggiore nel produrre un bel racconto epico piuttosto che una bella pastorale, un grande dramma piuttosto che una lirica perfetta. C'è un mordente molto maggiore nello sforzo intellettuale di creare un Bruto o un Otello, piuttosto che un Vicario di Wakefield o uno Squire Western (14) Più alto è l'obiettivo, più grande è il mordente e più nobile è il successo.

Queste, si potrebbe affermare, sono ovvietà, e in effetti lo sono. Eppure vanno riaffermate di tanto in tanto, perché gli uomini tendono a dimenticare che la dignità di un obiettivo elevato non può dare lustro a un'esecuzione imperfetta, anche se, in qualche caso, può attenuare il disprezzo che segue un fallimento. Solo il successo può reclamare il plauso. Qualsiasi sciocco può scegliere un soggetto elevato, e in generale la tendenza degli sciocchi è di scegliere soggetti che il grande ritiene troppo elevati. Se qualcuno è capace di saltare un ostacolo da cinque barre, il nostro plauso va alla sua abilità, ma se prova senza avere nessuna possibilità di successo, è destinato a cadere nel fango, e il nostro plauso va al fango. Tutto questo è troppo spesso dimenticato da critici e artisti, nella loro magniloquenza circa "l'arte elevata". Nessuna arte può essere elevata se non è valida. Un soggetto elevato cessa di esserlo se è trattato in modo debole. È un grande errore, com'è stato detto con arguzia, "credersi un grande pittore solo perché si dipinge con un grande pennello", (15) e sfortunatamente ci sono molti grandi pennelli in mano a degli incompetenti. Il povero Haydon (16) era uno della scuola del grande pennello; non era capace di dipingere un quadro piccolo perché non era capace di dipingere in generale, e credeva che coprendo una vasta area di tela stesse lavorando in stile elevato. In qualsiasi giudizio sul livello di un artista dobbiamo necessariamente tenere conto del soggetto e dell'eccellenza dell'esecuzione. È venti volte più difficile scrivere una bella tragedia che una bella lirica, ma è ancora più difficile scrivere una lirica perfetta piuttosto che una tragedia passabile; e c'era tanto buonsenso quanto sarcasmo nella risposta di Beranger quando il poeta tragico Viennet lo andò a trovare in prigione e gli disse che, ovviamente, tutto quel tempo libero avrebbe prodotto un bel po' di canzoni. "Credete che le canzoni si scrivano facilmente come le tragedie?" (17)